From service to scholarship: How Bethany Kibler inspires curiosity and critical thinking at UNCSA

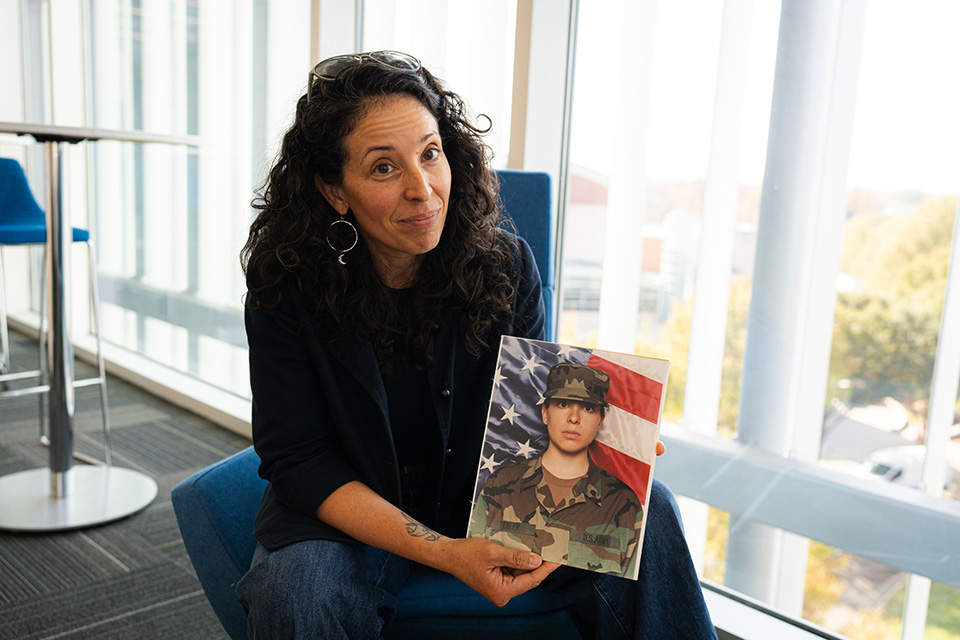

As a social anthropologist and Middle Eastern scholar in the Division of Liberal Arts (DLA), faculty member Bethany Kibler is the only U.S. Army Veteran among UNCSA’s full-time faculty.

Bethany Kibler with a photo of her from her early days in the U.S. Army. / Photo: Rugile Zemaityte

Kibler’s journey to academia wasn’t conventional. A native of Baltimore, Maryland, Kibler went to Pomona College in California for her undergraduate studies. “I chose it because it was across the country, she explains. “I had this strong feeling that I wanted to make my world bigger.”

While at Pomona, Kibler made the most of the liberal arts college environment, studying abroad in Italy, France, and Croatia; working as an editor at the weekly school paper; running a five-college Women's Union; and working on and offstage in plays and one-acts. She also explored many subjects, finally settling on creating her own major in French literature and philosophy and originally had a career goal of print journalism.

Expanding her worldview

Kibler’s time in college was also marked by the United States Presidential election in 2000 and 9/11 in 2001, two events that fueled Kibler’s desire to expand her worldview. “These events triggered my awareness of my own ignorance, of how little I knew of my own country and what was happening to it,” she explains.

Looking back, Kibler believes that this line of questioning and self-exploration is when she started thinking anthropologically. “I had all of this education, but suddenly felt totally at a loss to explain what the people around me – in my own country – were thinking or feeling. … It got me thinking about how I could change that, how I could learn more and expand my knowledge of the world.”

Kibler with her fellow basic training graduates in Fort Jackson. / Photo courtesy of Kibler

Kibler came from a long line of veterans and knew the educational opportunities that came with joining the military. Not long after graduating from Pomona, she enlisted in the U.S. Army as a Human Intelligence Collector and Arabic Linguist. In addition to 10 weeks of Basic Combat Training (“boot camp”), the preparation for the position included an 80-week course of intensive Arabic language training at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California and a 16-week course with the U.S. Army Intelligence Center of Excellence at Fort Huachuca in Sierra Vista, Arizona.

Boots on the ground

Her gift for teaching was quickly recognized and Kibler was recruited to return first as a Human Intelligence Field Training Exercise instructor and later as a classroom Interrogation instructor. During her three-year position as an instructor, she was deployed to Iraq as a team leader in tactical human intelligence collection.

In her role, Kibler helped create and run 24-hour, 7- to 10-day immersive war simulations in the Huachuca mountains on the Arizona/Mexico border. These large-scale, serious simulations were theatrical and included scripts, costumes and characters. “We had two mock-up villages, probably spread over a couple hundred acres, about two dozen role players, really basic costumes, this laser-tag-like equipment and some very low-grade fake explosives,” explains Kibler. “We'd write these elaborate 'war' scenarios to test and train our students.” As the scenarios unfolded, Kibler and her team directed role-players, adjusted scripts and adapted storylines in response to the students’ actions and training needs.

Bethany Kibler with her military certifications and awarded degrees. / Photo: Rugile Zemaityte

Kibler was also stationed in Baghdad during the height of the Army's Counterinsurgency (COIN) push. "That time was a very culture-centric approach to war that the Army higher-ups were pushing,” recalls Kibler. The culture-centric approach affected her in two different ways: First, because culture was seen as the key to winning the war, Kibler was in high demand as an Arabic linguist. Second, the COIN push meant that Kibler and her team were out in the city constantly – walking patrols, in people's houses, schools, hospitals and police bases almost every day. “The idea was that each unit should really get to know the people, build networks, and try to be a constant presence,” she explains.

Much of this experience frustrated Kibler and pushed her to seek a career focused on cross-cultural understanding in a non-military context – she felt like there was only so much cultural understanding and rapport she could build with the local population while in full armor and heavily armed. “It was so much effort but it felt pretty futile at the time,” Kibler recalls. ”Would getting the greeting right or using the polite form of address be enough to outweigh that we were literally occupying their city?”.

The path to anthropology

Kibler’s experiences in Baghdad motivated her to pursue a path where she could engage in the same work — learning about cultures and understanding people from vastly different backgrounds — but in a setting free from the constraints of being heavily armed. Inspired to further her education, she applied to Harvard University for a master’s degree in Middle Eastern Studies.

After a year at Harvard, Kibler decided to improve her Arabic. “I knew standard Arabic and some of the Iraqi dialect but I wanted to become essentially fluent,” she explains. Before long, she was studying intensive Arabic through a fellowship from the Department of Education in Damascus, Syria, where she also worked as a consultant and researcher for a Syrian arts nonprofit, helping identify the needs of young Syrian artists.

After completing her fellowship, Kibler returned to Harvard to finish her graduate degree and start a Ph.D. in Anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies.

As soon as she took her first Anthropology class, she was hooked “I'd found a community of scholars and a discipline that shared my sense that you can't just study culture from afar – you have to get to know people and become immersed in a place to understand more complex ideas or bridge more difficult divides.”

It’s about really hearing what people are telling you, situating those perspectives in broader historical or social contexts, reflecting on your own biases and the power dynamics that you bring with you to the field, paying super close attention to detail but also stepping back to see the whole, and then, at the very end, trying to find compelling and accessible ways to make all of that complex fascinating stuff accessible to people who weren't there with you.

Kibler on her love of anthropology

While anthropology can seem like a straightforward subject from the outside, Kibler believes the complexity lies in the balance of both subject and practice. “It’s about really hearing what people are telling you, situating those perspectives in broader historical or social contexts, reflecting on your own biases and the power dynamics that you bring with you to the field, paying super close attention to detail but also stepping back to see the whole, and then, at the very end, trying to find compelling and accessible ways to make all of that complex fascinating stuff accessible to people who weren't there with you.” Overall, this is a process that Kibler calls both exhausting and rewarding.

Halfway through her program, Kibler also took leave to work in Washington D.C. in student veterans advocacy, serving as the Higher Education Outreach and Research Fellow at the headquarters of Student Veterans of America. In this role, she also served as a direct mentor to hundreds of student veterans around the country, helped create a leadership curriculum for SVA's student chapters, and worked with university leadership and veterans support staff to enhance university programs and services for Veterans.

Building a bridge between experience and education

Kibler sees a clear throughline from her early interests in French literature to her time in the military to now as an anthropologist and professor at UNCSA. At the heart of her teaching philosophy is the idea that education should be a transformative experience, not a transactional one. It should be an experience that challenges students to question assumptions and develop a deeper understanding of themselves and the world.

Kibler teaching in the Division of Liberal Arts at UNCSA. / Photo: Rugile Zemaityte

"For me, it's all about expanding students' worlds, getting them to push beyond the limits of their experiences so far, working to break out of the limited ways we all tend to think about the world and ourselves,” she says. She feels her role is not to hand her students all the answers but to help them ask the right questions. “I try to get students to sort of move away from following instructions and doing what they're told or working within the parameters of someone else's vision,” she explains. “I want to help them start building the skills that allow them to generate their own work, their own projects, and think ‘what do I want to do, and how do I do it?’”

This focus on critical inquiry is where she sees the connection between her work and the arts. By combining analysis with creative exploration, she provides her students with a comprehensive learning experience that prepares them for a variety of fields. “Every student is different, and each brings something unique to the table,” Kibler says. “What I'm trying to do in my classes is to get my students to really think about the creative process. It doesn't matter if the skills learned are for an essay, or a piece of choreography because there are very similar lessons learned of self-assessment, brainstorming and reflection.”

What I'm trying to do in my classes is to get my students to really think about the creative process. It doesn't matter if the skills learned are for an essay, or a piece of choreography because there are very similar lessons learned of self-assessment, brainstorming and reflection.

Bethany Kibler

In teaching, Kibler also draws on her military experience. “One thing that was very eye-opening to me in my military educational environment was realizing that for many people, their relationship with secondary education was one of deep alienation and unease,” she explains. But most importantly, military education taught her the benefit of failure. “In the military, you fail constantly – publicly and spectacularly. And eventually, it’s just not a big deal,” she says. “You learn that failure is part of the process of improving.”

Kibler’s journey – from receiving a liberal arts education to the military to Harvard to teaching in a liberal arts program and all the stops in between – has been fueled by a constant desire to enhance her understanding of the world around her. Along the way, she’s helped countless students – from student veterans in Washington D.C. to artists at UNCSA – learn to push themselves that one step further.

By Melissa Upton-Julio

Get the best news, performance and alumni stories from UNCSA.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTERS

November 11, 2024