Hellraiser and innovator: Bob Keen on sneaking into the film industry and inspiring the next generation

For Bob Keen, “breaking into the film industry” was a literal feat. At 15, he snuck through a hole in the fence of an England studio lot and charmed the security guard, which set the scene for a career in visual effects and filmmaking spanning more than 40 years.

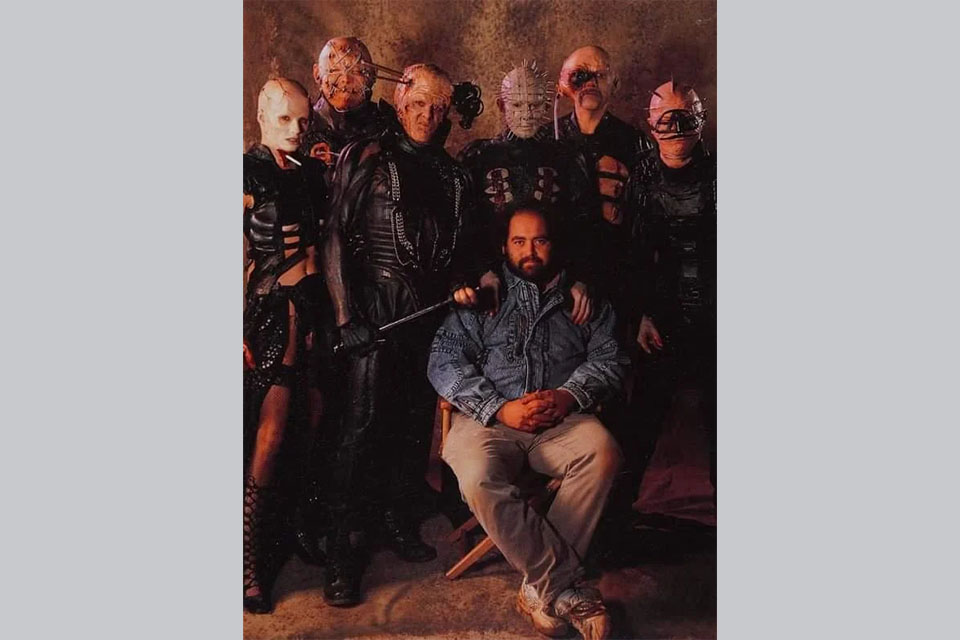

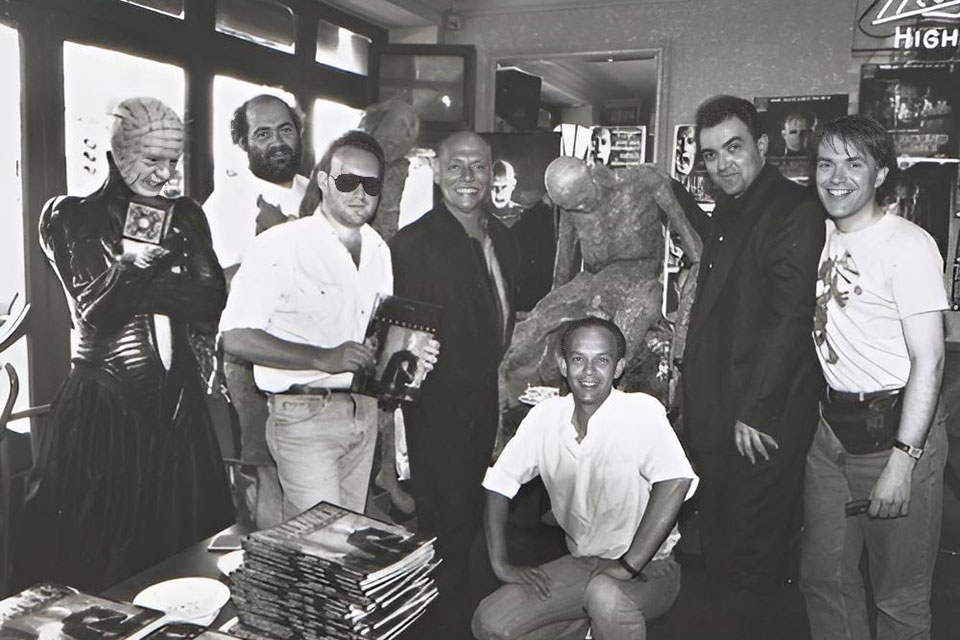

Keen, who earned “Hellraiser” as his middle name after his work with the British-American horror franchise of the same name — and no doubt thanks to his boundary-pushing nature — now teaches the industry’s up-and-coming innovators in the School of Filmmaking.

As chair of the Visual Effects department for seven years and Director of Visual Effects and Immersive Media, Keen has helped develop the Immersive Entertainment program while also leading the Media and Emerging Technology Lab (METL), an immersive storytelling incubator, alongside METL Producing Director, Stacy Payne.

Most recently, Keen, School of Filmmaking Dean Deborah LaVine and Art Direction faculty member Burton Rencher have launched the Story Art Studio (SAS), a new three-year discipline offered through the school to foster multi-skilled graduates.

Students enrolled in the first term of SAS are getting a crash course in experimental storytelling and visual effects, mixing old and new tools to explore different ways of telling sophisticated, emotional stories with heart.

“It’s certainly giving them a window to the world, and any time that you have an opportunity to see more of the world, you have more of an opportunity to grow inside,” says Keen. “As you grow inside, you become a different person, and that’s what the hope is.”

That’s certainly what happened for Keen at 15.

Breaking onto the scene

“What do you want to do?” Shepperton Studios’ security guard asked Keen after catching him climbing through the fence a third time.

“I want to be in special effects,” the tenacious teenager Keen replied. A train ride and bus trip across London, and a two-mile walk to the studio hadn’t shaken his determination, and the guard wouldn’t either.

Nearly a decade earlier, Keen’s father had taken him to see “Thunderbirds Are Go,” a science-fiction film featuring puppets and based on a television series. Recognizing his interest, his father later gifted him a book about miniatures, or scale models, and magic.

Intrigued by Keen’s passion, Shepperton’s guard asked the film crew working at the studios if the teen could observe for an hour.

“They had these fantastic miniatures they were shooting,” recalls Keen. “Everyone got interested in this story, that I went around the back of the studio three times and was determined that much to do it. And they said, ‘Can you make tea?’ … So I became the tea boy on this film.”

Soon enough, tea would turn to fireballs. Tasked with making a volcano erupt on the film set, Keen was even more hooked on special effects and made good industry contacts.

Training with Jedis

Keen took odd jobs, creating miniatures and repairing helmets, before hitting his next big break with “The Empire Strikes Back,” a sequel to “Star Wars.”

One of his contacts, British special effects director Brian Johnson, told him he had a few weeks of work for him. From there, Keen was linked with Stuart Freeborn.

Two legends: Bob Keen and Yoda from the "Star Wars" franchise. / Photo: Mark Jabourian

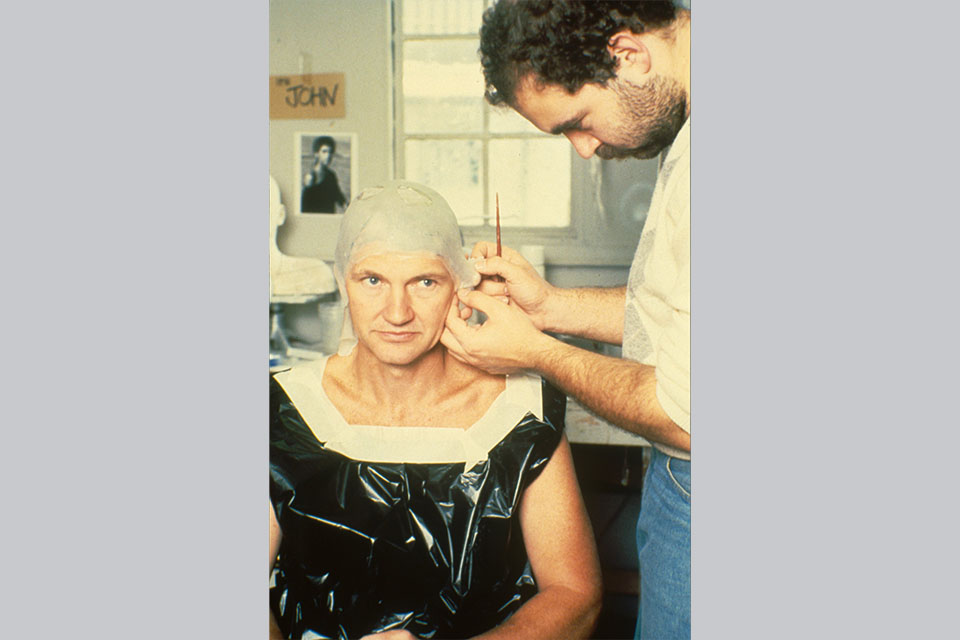

“Stuart was this wonderful, wonderful make-up artist who did prosthetics and made creatures,” explains Keen. Under Freeborn’s wing, Keen worked on Yoda, as well as tauntauns, or snow lizards, and other creatures in the film, earning him his union ticket.

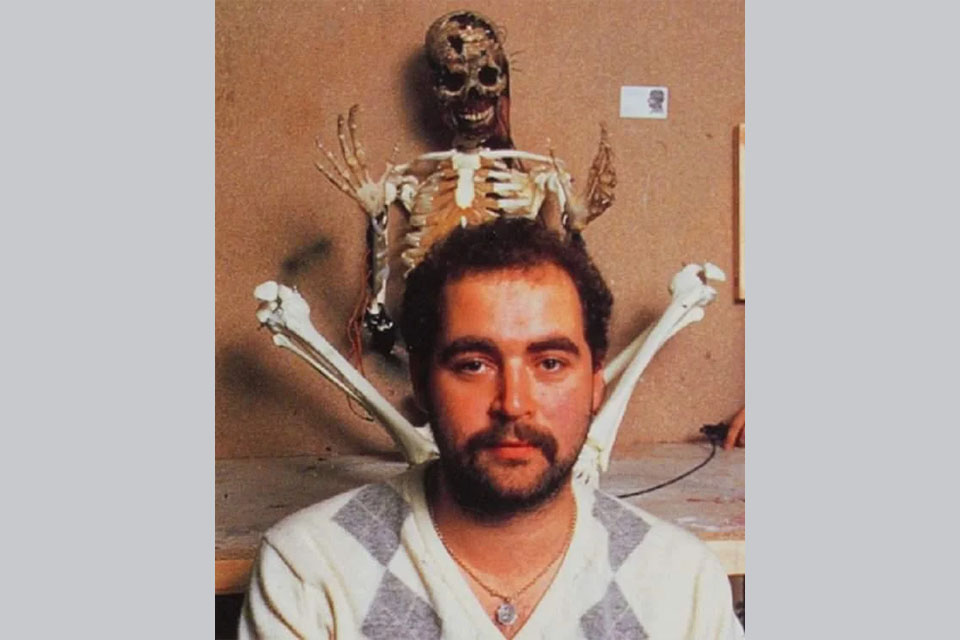

Keen went on to work on iconic films like “Never Ending Story,” “The Dark Crystal” and “Return of the Jedi” before starting his own special effects company, Image Animation PLC.

At its peak, the company had 150 technicians and operated out of international branches in Los Angeles and Toronto, in addition to its home base at Pinewood Studios in England.

Entering new territory

Two decades and more than 250 films and TV projects later, Keen found himself juggling newfound parenthood and a busy career in film.

“On my son’s second birthday, I realized I’d only been home for 19 weeks,” remembers Keen. “So I said, “OK, this is going to change.”

Keen sold his company and ventured into film consulting, moving first to Texas and eventually landed in Winston-Salem.

Keen quickly got a call from the UNCSA School of Filmmaking.

[My students] are the enthusiasm that just lifts you up and gets you going and makes me want to go to work every day.

Bob Keen

“‘Are you Bob Keen? Your wife phoned up about two months ago, and we’ve looked up who you are and have been trying to get hold of you,’” Keen recalls hearing.

And get a hold of him the school did. Keen started as a lecturer and planned to stay on for the year. Now, 13 years later, Keen maintains a reputation of being both a beloved faculty member and living legend to his students.

“I really enjoy the aspect of giving back the knowledge that you gained,” Keen says of his teaching journey. “I had a lot of apprentices in my company, and the process is very similar in that you see these young people who are incredibly enthusiastic. They are the enthusiasm that just lifts you up and gets you going and makes me want to go to work every day.”

Who cares wins

That keen spirit is at the heart of his work in the School of Filmmaking, with METL and now SAS, as Keen works to bridge the two programs to optimize students’ learning.

“The Story Art Studio is something different, something new,” says Keen. “It’s a cluster of experimental classes trying to give students opportunities – not so much in the “I’m a director” or “I’m a cinematographer” – but more of that they are creators, and they are using their imagination and multiple skills, working very closely together as a team to create things that are different.”

SAS students will lean into METL’s community outreach approach to explore local myths and legends, uncovering how storytelling is just as important as the stories themselves.

Keen teaching in the "The Cube" located in the Center for Design and Innovation in Winston-Salem, the home of METL. / Photo: Wayne Reich

“Part of the challenge is we’ve been bombarded in the last couple of years by movies that have really gone to this point where everything is super complicated and cutting is super fast, and we’re flooded with information,” explains Keen. “What we’re trying to do is step away from that and say, ‘Let’s get to the quality of the image, not the quantity. Let’s concentrate on what really tells the story.’”

“Our motto at Story Art Studios is ‘Who Cares Wins,’” says Keen. “A lot of our projects are connected to strong emotions … strong meaning, and a strong sense of doing something.”

Exploring local stories, like METL’s work with the Winston-Salem African-American Archives, “exposes a whole gauntlet of stories and levels of stories that are out there in the community that we don’t even see,” he said.

This work will send students out into the community to conduct interviews and consider how to tell others’ stories.

“Students will explore these stories in different ways,” says Keen, “whether it’s an unusual way of doing a documentary, or if that’s a way of expressing some inner emotions that they haven’t been able to express before, something about themselves.”

All that glitters is not gold

As technology advances, more storytelling tools emerge, leading to endless possibilities and, for Keen, a heightened importance of keeping the heart of the story in focus.

“We are constantly having new and glittery toys come along,” explains Keen. “What happens is we sort of rotate to those ideas or techniques, and sometimes that’s absolutely what we need to be doing.

“But someone told me this right back when I was in that first studio, in the tea boy stage of my career: ‘If you can do it with a piece of string and a rubber band, do it with a piece of string and a rubber band.’”

Bob Keen teaching students from the UNCSA School of Filmmaking. / Photo: Wayne Reich

Keen is no stranger to computer-generated effects or artificial intelligence, if those are the right storytelling tools, but that lifelong string-and-rubber band philosophy has helped him find balance between new and old and a fascination with exploring all possibilities.

“One of my favorite things to do is use the most inexpensive thing – a Post-it note – and we write ideas up and we stick them on this $95,000 LED screen,” says Keen. “You stand back and you start seeing the shapes of things and how things work.”

Keen believes this visual sense of looking at a problem and thinking of new approaches creates a natural rhythm.

“Strangely enough, I find the students get as much out of that and finding that that works as they do out of exploring with the highest technology,” Keen said. “Visual storytelling is an art form, and we’re visual creatures. We like to see things, and when we see something, other ideas happen. My favorite moment with students is the moment where the light bulb comes on, and they say, ‘I can think free. I can explore.’”

This exploration not only imparts filmmaking and visual effects skills but also teaches students to think creatively and adapt quickly.

“I’m a great believer that you need to teach people to think, not to do one particular thing,” Keen said. “If you teach them how to put on prosthetic make-up, or if you teach them how to do digital effects or teach them how to do miniatures, they will just know how to do that. Really, what I try to teach is to get them to be problem-solvers and to think in a way of anticipating what a problem is and heading it off before it happens.”

I believe that the future is probably more of a jack of several trades than a jack of one trade. What I hear most from people in the industry is that they want new ideas. They want innovation.

Bob Keen

For Keen, there may be 20 or 30 different approaches to problem-solving and no one way is the “right” way, but what’s important is adapting when one approach doesn’t work.

“You can’t do original work without…I don’t want to say failing, but it is,” says Keen. “It’s being able to go down a road then adjust. Original work comes not from stepping on the same ground as so many others.”

Trying new paths and looking at problems in new ways has always been critical in the film industry. “I believe that the future is probably more of a jack of several trades than a jack of one trade,” Keen said. “What I hear most from people in the industry is that they want new ideas. They want innovation… The industry itself is changing and transforming on a daily basis, and it needs people who can think fast and have new ideas. We’re training those people.”

So, Keen is helping his students look for their own figurative hole in the fence. All it takes is a little hell-raising and storytelling magic.

Get the best news, performance and alumni stories from UNCSA.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTERS(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(opens in new tab)

September 26, 2024