Oscar-winner Troy Kotsur shares career highlights and future aspirations at UNCSA

“Educate hearing people, but not preachy, with a sense of humor and a little middle finger behind it.” That’s Academy Award-winning actor Troy Kotsur’s platform, as ASL interpreter Justin Maurer described in a recent Q&A session with Kotsur at UNCSA, made possible by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts.

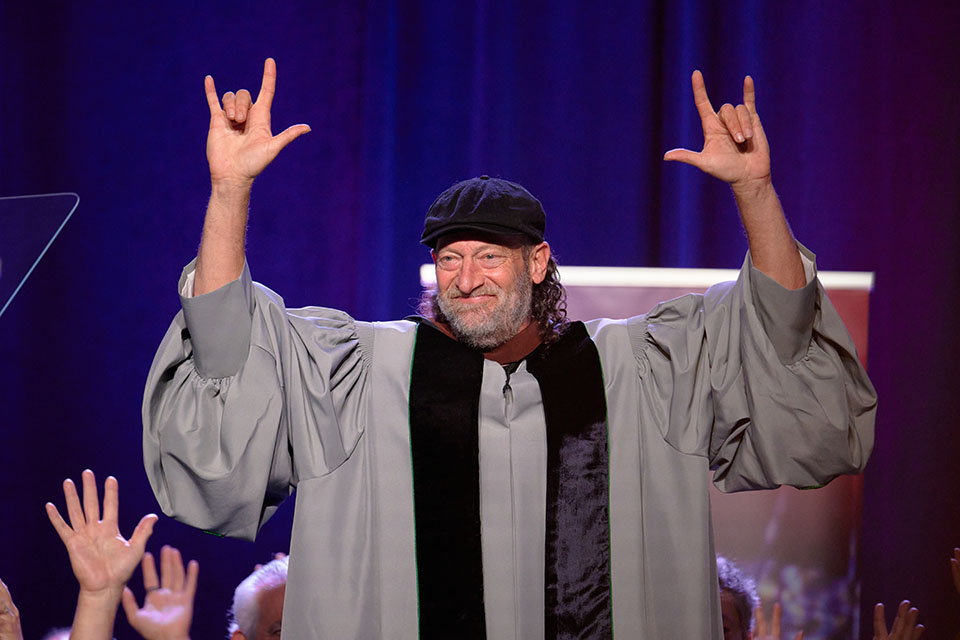

Since his groundbreaking role in “CODA,” for which he became the first deaf male actor to win an Oscar, Kotsur has become an “overnight sensation.” He’s been featured on countless shows, was on the cover of Variety magazine, has been the keynote speaker for numerous events and, of course, was the 2024 commencement speaker for UNCSA.

But behind Kotsur’s recent notoriety is two decades of incredible acting and directing experience. On May 17 — just a day before commencement — students at UNCSA had the opportunity to learn first-hand about Kotsur’s career in a conversation hosted by School of Filmmaking Dean Deborah LaVine, who has worked with Kotsur for years.

True to his platform, Kotsur quickly had students laughing and feeling comfortable asking questions about inclusivity in the industry. With Maurer interpreting, he shared key moments from his career, his work translating English to ASL, the role of an ASL interpreter and his hopes for the future. Along the way, the audience gained invaluable insight into the world of storytelling and, as Kotsur phrased it, learned “a little bit about how to work with an actor who happens to be deaf.”

Finding authenticity

Early in his career, Kotsur began working at Deaf West Theatre in Los Angeles, known as “the artistic bridge between the Deaf and hearing worlds,” where deaf actors and hearing actors perform together. Here, Kotsur met Dean LaVine and collaborated on several productions. He told the audience about one experience in particular that helped shape him as an actor: playing Stanley in “A Streetcar Named Desire,” directed by LaVine.

Troy Kotsur as Stanley in Deaf West Theatre's "A Streetcar Named Desire," directed by Dean of Filmmaking Deborah LaVine / Photo: Lawrence K. Ho & Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

The role of Stanley — iconized by Marlon Brando in the 1951 film rendition of Tennessee William’s famous story — was typically approached with a level of grit and macho that Kotsur found a bit too obvious. “I struggled with it. I didn’t want to look like someone else’s depiction of this character,” he explained.

When he went to LaVine for help, she told him one simple thing: “Troy Kotsur is Stanley, Stanley is Troy Kotsur.” For that night’s performance, he decided to throw everything out regarding his character and just be himself. On LaVine’s advice, he played the role more simply and authentically. “That night really made a big impact,” he said. “The audience had a strong reaction and afterward Deb came up to me. She tilted her head and had a big smile on and just said, ‘Yes.’”

Kotsur told the audience that as an actor, it’s critical to stretch your capabilities and not be afraid of making mistakes. “There’s always another chance, especially with the theater stage,” he said. “You can try something different the following night, make it organic and natural and listen to what people are telling you.” This approach was so successful that Marlon Brando called to say he wanted to see the show — he’d heard Kotsur was now the definitive Stanley.

Merging languages

Another element of Kotsur’s work as an actor is translating scripts into ASL. “So a script is written in English,” he explained. “Sometimes, when you’re signing, it’s not in order because of the syntax and grammatical structure of ASL. You have to make these small adjustments.” He said one of the challenges is finding the right tempo to align the spoken English and ASL lines.

Then there’s matching the tone. To demonstrate the importance of tone in ASL, Kotsur signed three different levels of “I love you” for the audience. “You see the difference and the levels? You can do the same thing with vocal intonation,” he explained as Maurer vocalized three different intensities of “I love you.” “With the voice actor and the deaf actor on stage, you work together to make those adjustments and match each other’s emotions.”

Troy Kotsur holding up the sign for "I love you" at the 2024 UNCSA Commencement / Photo: Wayne Reich

These adjustments in tempo and tone are generally made during the rehearsals, which Kotsur insists on even for TV and film projects. But having multiple languages like ASL and spoken English is a process most companies are still honing. “On my contract, I require an ASL team because if I sign a mistake and don’t follow my line, how will the script supervisor know?” he explained. He said a “Deaf eye” can work with the script supervisor to bridge the two languages, translate any improv he makes, ensure the sign and script align, and assist the editor in post-production.

Kotsur told the audience that his experience on set and stage is reminiscent of his childhood. “Growing up, I was on a baseball team with all hearing players. I was a little bit nervous, of course, and the hearing kids were nervous wondering, ‘What are we going to do with the deaf baseball player?’ But by the last day, we were all signing and were good friends.” This process was repeated when he joined the football and basketball teams, and he said it was a similar experience in film, TV and theater. “The hearing team is a bit timid at first, but by the last day, we’re all getting along and communicating. You learn on the job and as you go.”

Where’s the interpreter?

For the past few years, Maurer has worked with Kotsur as an interpreter, providing a consistent voice for the interviews, screenings, and panels that followed the success of “CODA” and helping to translate on set. “I’m just working with Troy when he’s working, communicating with hearing directors, hearing cast members, crew, fittings — everything,” Maurer told the audience. “As an interpreter, I’m part of the crew and you have to do the dance when you’re part of the crew — I’m out of the way, I’m not in frame, I’m in the right position. Sometimes it’s really cramped, sometimes I’m laying on the floor, sometimes I’m standing on a shelf, sometimes I might have a flashlight.”

And sometimes, the situation is a little more perilous. “We worked on ‘Running Wild with Bear Grylls,” Kostur shared. “It was unpredictable what was going to happen next. I had to repel a 300-foot waterfall and at one point I was stuck in the middle. If I was hearing, they could yell to me or use a walkie-talkie or something. But I’m deaf, so I was like, ‘Where’s the fucking interpreter?’ And I look up and see Justin repelling down the edge of the cliff to sign something to me. There’s crewmen literally feeding the interpreter down the mountain on a rope.”

But beyond interpreting language on film sets and over cliff edges, Maurer must also understand Troy’s sense of timing, his humor and his pathos. “It’s really important that I’ve had this same interpreter for a while who really understands my way of thinking,” explained Kotsur. “We’re on the same page and it gives me peace of mind. We’re a good team.”

Hollywood, open your mind

In the numerous productions and projects Kotsur discussed, ASL consistently helped bring the story to life, like performing the National Anthem alongside Chris Stapelton at the 2023 Super Bowl and creating a sign language for the Tusken Raiders in “The Mandalorian.”

“There’s a lot of benefits to sign language,” he said. “You can sign underwater, you can sign through windows, make secret codes and so on. We need to approach this in ways that are entirely new.” As Kotsur’s fame increases, he’s been asking Hollywood to open its mind. “In all of these meetings, I’ve been telling them that I’d like to play a role that people have never thought of.”

He gave the audience an example: “Have you ever considered a rodeo rider who happens to be deaf? Have you ever seen that before?” Soon, audiences will be able to answer “yes” to that question — Kotsur just wrapped an independent film called “In Cold Light,” where he plays a deaf rodeo rider in a feature film. “So I can check that off the bucket list,” he said.

They’re finally listening, and we can share our rich Deaf culture of sign language with the world. We can give them more stories to tell and create so things become even better for the next generation of deaf actors. It’s amazing that winning this award really made an impact on the world.

Troy Kotsur

While there’s still a lot of work to be done, Kotsur said winning an Oscar has opened new doors. “The Oscar recognition really gave me a bit more power, so there’s more respect from writers, directors and producers. They’re finally listening, and we can share our rich Deaf culture of sign language with the world. We can give them more stories to tell and create so things become even better for the next generation of deaf actors. It’s amazing that winning this award really made an impact on the world.”

Learning on the job

The road to the Oscars wasn’t always easy for Kotsur. He told the audience about the years he spent as a struggling artist, and how his wife — also an incredible actor who is deaf — often taught to pay their bills. “Imagine plucking a hair out of my beard, and this one hair was the odds of success, right? That’s how I felt,” he said. “But it was really just a matter of time, and I just had to keep going and keep working.”

Kotsur said he learned on the job with wonderful leaders like LaVine. “You’re so lucky to have Deb,” he told students. “You have wonderful leadership and wonderful teachers here. A big part of who I became today is because of her wonderful leadership, and I’ll never forget that.”

Troy Kotsur and Dean of Filmmaking Deborah LaVine at the 2024 UNCSA Commencement / Photo: Wayne Reich

His advice for aspiring actors? Build your skills and always read the entire script. “On the theater stage, you can build and grow. What I learned from stage really helped me have a better understanding on set for TV and film, and improv was also a big help. It’s nice to have all of those skills and helps you find more jobs.”

Today, Kotsur is able to live back in his home state of Arizona after years in Los Angeles. He told the audience, “This time, Hollywood knows where to find me.”

Get the best news, performance and alumni stories from UNCSA.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTERS

June 20, 2024