The storied career of Liberal Arts Dean Rachel Williams

Growing up in Eastern North Carolina, Rachel Williams did not dream of becoming a comic book creator, but a Google search result describes her that way. Dean of the Division of Liberal Arts at UNCSA, Williams is the author of two graphic nonfiction books exploring social and racial injustice, both published in 2021. But that is only one chapter in the life story of an artist, scholar and educator.

Chapter One: The Artist

“I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t making art,” Williams says. “By age seven or eight, I knew I wanted to be an artist. By high school, I couldn’t imagine being anything else.”

Her passion for art led Williams to East Carolina University, where she earned a B.F.A. in painting and drawing, and then to Florida State University, where she earned both an M.F.A. in art studies and a Ph.D. in art education. Over the next two decades, Williams taught at high school, undergraduate and graduate levels and held several leadership positions at the University of Iowa, all while continuing to make art. Her interests include painting, drawing and printmaking.

Dean of the Division of Liberal Arts Rachel Williams / Photo: Amber Renea

“I dabble in different methods depending on the image,” she says. She also enjoys painting landscapes outdoors and, of course, creating graphic narratives. A gallery of her work graces her website.

“I didn’t grow up reading comic books about superheroes,” Williams says. She was familiar with the “American Splendor” series by Harvey Pekar. “They were comics about real life, an ethnographic way of storytelling.” Pekar’s work spanned more than 30 years ending in 2008, depicting moments of his life – his work, his relationships with family and friends and the challenges of everyday life. His philosophy was, “Graphic novels are words and pictures. You can do anything with words and pictures.”

Williams fully embraced the concept. “I had a light bulb moment. You can describe a person in words or draw the person. It is an interesting way to think about storytelling, combining images, text and design.”

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t making art. By age seven or eight, I knew I wanted to be an artist. By high school, I couldn’t imagine being anything else.

Rachel Williams, Dean of the Division of Liberal Arts

Interviewed in 2015, she explained, “There is something that is reached in your brain when you draw that isn’t as easy to articulate through language.”

Readers have a much different experience reading comics, Williams says. “Graphic novels help people understand a story in a way that text alone doesn’t. Reading comics is a more complete experience than reading a book,” she says.

Chapter Two: The Scholar

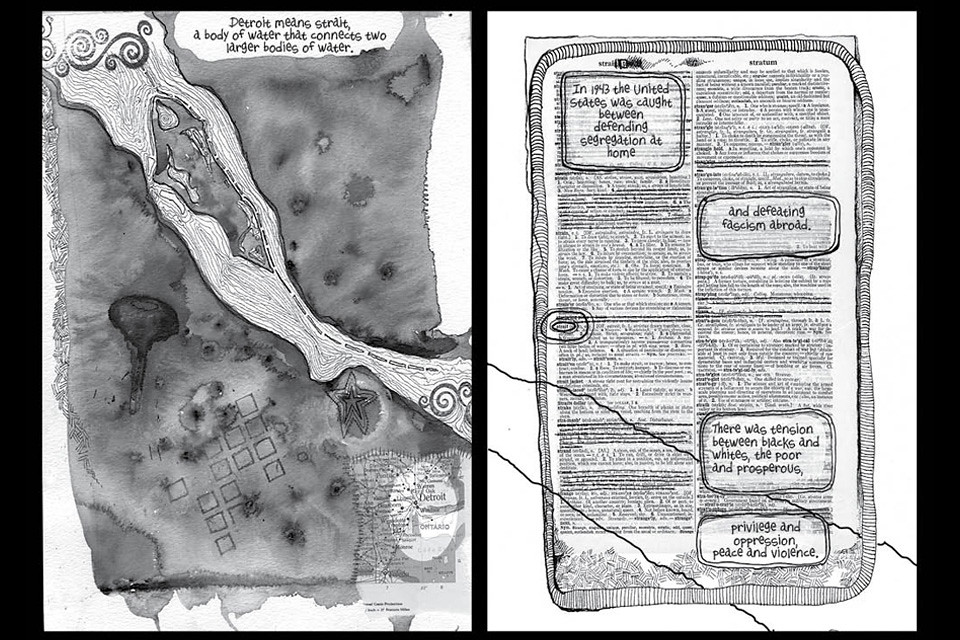

Graphic storytelling became the center of Williams’ work as a researcher and creative scholar focused on women’s issues, community, art and incarcerated individuals. Her published books include “Run Home If You Don’t Want to Be Killed: The Detroit Uprising of 1943,” which she describes as a “grim depiction of racial violence and what led up to it.” The book has earned 4.5 out of five stars on Amazon and a reviewer said the work was “beautifully illustrated, engaging and provocative” with “artwork that readers won’t soon forget.”

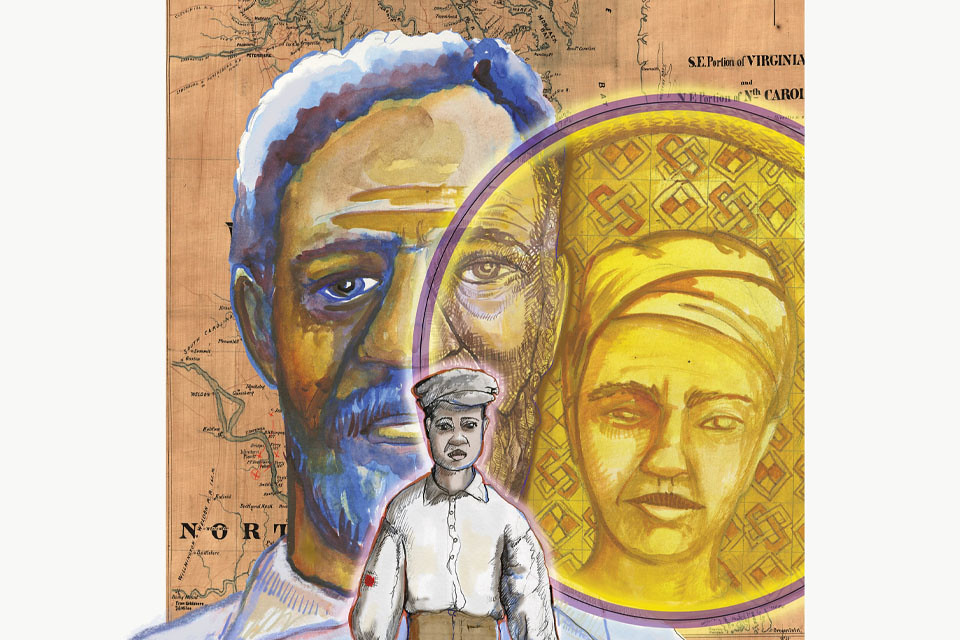

Williams’ second book, “Elegy for Mary Turner: An Illustrated Account of Lynching,” described a 1918 episode of racial injustice in Georgia. With a five-star Amazon rating, the book was reviewed by NPR, which noted, “Williams doesn’t just deplore unspeakable evil or try to argue with it. She confronts it in its own realm – the realm of art.” And a reader said, “The way the story is told, even with limited words, lingers with the reader for quite some time.” To create the illustrations, Williams used the process of lino-cutting, a printmaking technique in which a design is cut into linoleum (rather than wood) to create a reverse image of the final print.

“It is unique in that way,” Williams says. “It is considered an artists’ book.”

Chapter Three: The Educator

Williams’ passion for art is matched by her passion for teaching. She taught for more than two decades at the University of Iowa, including dual appointments in the Department of Art and Art History and the Department of Gender, Women’s Studies, and Sexuality Studies. “I’ve taught so many things, I’m like a housefly,” Williams says, listing gender studies, graphic novels, research, film theory, introduction to social justice in addition to drawing, painting and other visual arts.

She also served in several leadership positions at the University of Iowa, including University Ombuds in the office of the president. “Being an ombuds helped me learn to look at situations from various points of view and with the lens that different stakeholders have different pieces of any story and different needs/concerns,” she says. “In other words, to look for complexity.”

Dean Rachel Williams teaching a Liberal Arts course. / Photo: Summer Sierra

Williams has also volunteered for more than 20 years as a teacher to incarcerated women, men and adolescents, introduced to the opportunity by an instructor in her undergraduate program. What began during a semester break sparked another lifelong passion.

“That’s where I learned how to be a good teacher,” Williams says in a 2011 interview for Women at Iowa, a video series highlighting women on the faculty. “When you have adult students who are there for the sheer joy of learning rather than because they have to be there or because they are paying to be there in order to earn a degree, it’s a really different dynamic. It’s an honor to teach students like that.

“Coming out of art school, I was in a very cynical point in time,” she continued. “I had a really jaded idea about art and the purpose of art in the world. Going into the prison, I was able to see that the women there made art because they needed to make art and they wanted to make art, and they made art that was meaningful to them and their families. It was really exciting and refreshing to see that art is a real thing and that people really do have to make art.”

The art made by Williams’ incarcerated students included basic portrait painting and creating graphic and video memoirs, which helped them understand dynamics of their relationships and consider ways to stop cycles of poverty and abuse. Looking back on the experience, she recalls that “they were overwhelmingly poor from tough socio-economic circumstances. I tried to make the classroom experience what they wanted it to be. They wrote the curriculum."

Chapter Four: The Dean

In her first year as dean, Williams taught a course about the history of social movements. As her second year begins, she regrets she won’t have time to teach but is invigorated by the administrative work ahead. She leads a full-time faculty of 14 who teach courses in composition, foreign languages, history, humanities, literature, mathematics, media studies, philosophy, psychology, science and writing. “I love Liberal Arts and I love the faculty,” she says. “They are amazing people who see very broadly that art ties into history, ethics, science, literature and writing.

Dean of Division of Liberal Arts Rachel Williams (left) with Executive Director of the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts Kevin Bitterman (center) and and Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Patrick Sims (right) at the 2023 UNCSA Chancellor's Circle Dinner/ Photo: Wayne Reich

“I have a passion for research and I’m pleased to support the faculty in their research,” she adds.

As a dean, an artist, a teacher of artists and a teacher of those who teach art, Williams wants students to understand the power of art in everyday life. “You might not make it to Broadway. You might never appear in a movie. But you will be making art,” she says. “People are making art in every corner of the world, every day. It’s a powerful thing.”

Williams’ benchmark is Mel Stanforth, a professor of art at East Carolina. “He was so kind. He had a great sense of humor,” she says. “He was always warm to students, but he was also rigorous. I felt valued as a student. As a teacher, I hope to let students know how important they are and the value of what they bring to the class.”

Epilogue

Williams embraces the labels of artist, scholar, educator and comic book creator. The biography on her website offers a few additional labels:

- predatory baker —“I love to bake but I don’t like to eat much in the way of sweets so I often foist baked goods onto unsuspecting others.”;

- motorcycle maven — She rides a 750 BMW GS with a favorite riding partner, her husband Don; and

- mother — Rylie, 20, is a senior at the University of Iowa in printmaking/psychology; Jack, 18, is a junior majoring in astrophysics at Iowa.

Get the best news, performance and alumni stories from UNCSA.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTERS(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)(OPENS IN NEW TAB)

August 08, 2023