Robert Gipe

Listen to the interview on Apple, Spotify, or your listening platform of choice. Captioned interviews are available on YouTube.

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

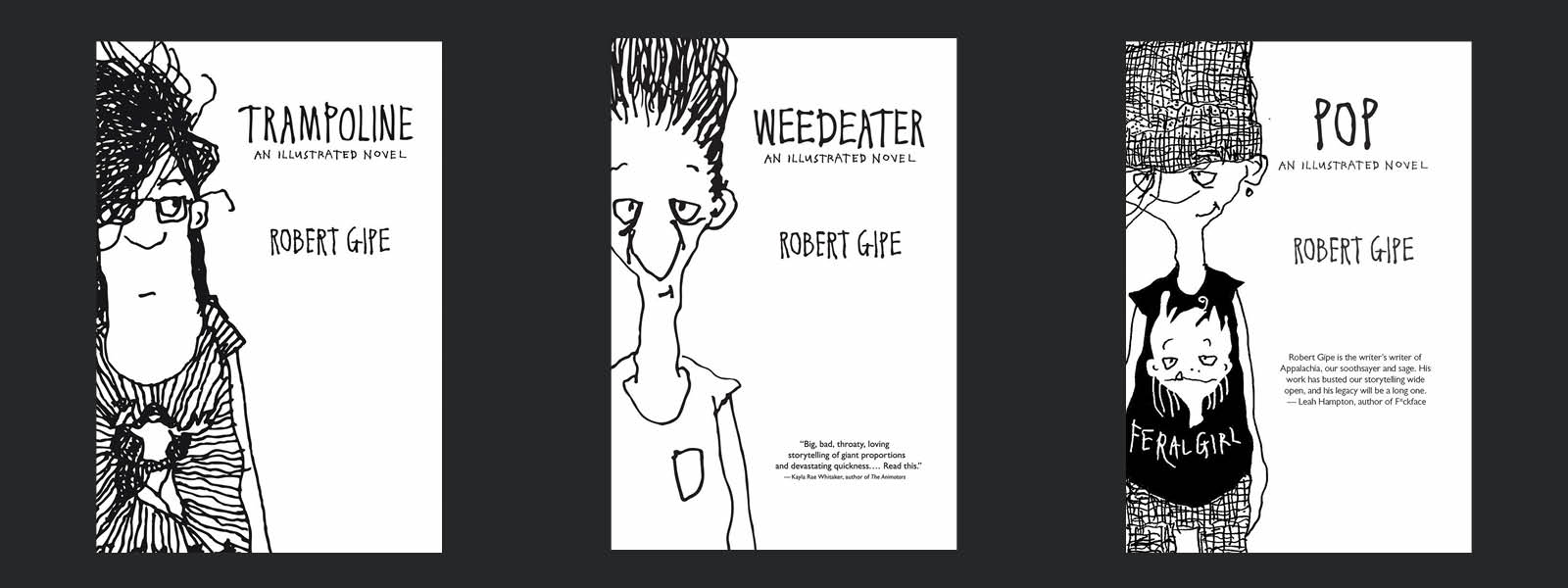

Calling Robert Gipe an author or novelist is a bit like calling Neil deGrasse Tyson a YouTuber. Yes, Robert wrote a widely praised self-illustrated trilogy of novels — “Trampoline,” “Weedeater” and “Pop” — that follows the travails of a young woman growing up in rural Appalachia. He completed that authorly feat, however, after decades working as an educator, community builder and theater-maker in and around Harlan, KY, where he continues to reside.

Originally from Kingsport, TN, Robert moved to Southeastern Kentucky in the late ’90s after receiving his master’s in American studies at the University of Massachusetts. Initially he worked in marketing and fundraising for the legendary community media organization Appalshop in Whitesburg, KY and then became a professor and program coordinator of the Appalachian Center at Southeast Kentucky Community & Technical College in Cumberland. Soon thereafter he created Higher Ground, a community theater organization that since 2002 has created and produced plays with and for the community on local topics ranging from opioid addiction to environmental degradation.

In this candid interview, Robert describes the challenges of encouraging community-wide fellowship in a politically divisive era and celebrates the role of art and artists in creating safe spaces for people of all stripes to celebrate their authentic selves.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- When and how did you create Higher Ground?

- When did you start thinking of yourself as an artist?

- How have you handled politics throughout your career? Do you welcome or prevent politics from entering your artmaking and the discussions around it?

- What role do you think art should have in a smaller rural community? You talked about holding space, but how else can it be truly useful to a smaller community?

- What needs to change so that there are a thousand Appalshops in rural communities around the country?

- What advice would you give to an artist about making an artistic life in a small rural community?

Pier Carlo Talenti: Tell me about when and how you created Higher Ground.

Robert Gipe: In 2001, I had been involved for a year or two at that point with about 10 or 11 other people who were doing Appalachian Studies programming. These are all people at four-year schools, places with graduate schools. We had been in conversation with the Appalachian Regional Commission, which is a federal agency centered on improving conditions in a federally defined Appalachian region, which spreads over 13 states.

We collectively, me and these other faculty types, came up with a project called the Appalachian Teaching Project, where we each had a single class. They knew they were going to come to Washington and present on work around how to make for better living conditions in the given community.

Pier Carlo: Oh, so there was a trip and a presentation to Washington that was part of the program?

Robert: That’s right. Yeah, it’s still going.

We were the only college that was located in what the A.R.C. defines as a distressed county, and we were supposed to focus on a single distressed county. You earned the name distressed by having 150% of the national poverty rate and 150% of the national unemployment rate. We were the only college located in a distressed county, and so we studied ourselves. The students came up with plan for building on our assets to address our challenges. Cultural production was one of the main things they thought we could build on and use to address our challenges.

The following school year, we did a community-based process that was powered by a lot of the community members who were in those classes to respond to a request for proposals from the John D. Rockefeller Foundation to use the arts to respond to a particular challenge that your community was facing. We did a bunch of surveys and talked, just had a bunch of community conversations. Then me and another faculty member and about 40 community members worked together to write a proposal that talked about using theater and photography and public art as a way to respond to the opioid crisis.

We got that grant in 2002 and worked with a series of professional theater artists, Jo Carson as a playwright and Gerry Stropnicky as the director, to create a musical in response to the Oxycontin and opioid crisis. I think that first one had north of 80 people in it. It was a big beginning. All the photography work that we involved … it was right at the end of the film era, and so we had 600 people using disposable cameras to create a visual of the community, and we built a couple of tile-mosaic public-art pieces in collaboration with our ceramics department at the community college.

By the end of that project in 2005, I think we’d involved 2,000 community members in creating stuff. That was the big bang that helped us define programming. We just finished our 10th play, which we did as part of a national festival called One Nation/One Project, Arts for EveryBody that was about arts organizations working with healthcare organizations to look at how arts could contribute to community wellness.

Pier Carlo: I interviewed the two founders of that project last year! It’s amazing.

Robert: Yeah, well, they got it done.

Pier Carlo: That’s incredible. It must have been one of the earliest projects that they accomplished.

Robert: Well, they did. They had 18 partners, and I think all 18 did something on the same day.

Pier Carlo: Wow, that’s incredible.

Robert: On July 27th. Yeah, that was great to be a part of. I think that we got to be a part of it because of this kind of legacy of stuff that we had done.

Pier Carlo: Did you consider yourself an artist all along? Or when did you start thinking of yourself as an artist?

Robert: Well, as an English major, I never took a creative-writing class. I always drew, but I never really took art classes with any intention. I thought I would be eventually, but I didn’t really think I was.

In my career at Appalshop, I did a lot of brokering. Early on, the first big grant I got in 1990 paid my salary, and it paid us to buy this exciting new product called VHS video. It was the first time that all these 16-mm films that Appalshop had been producing were available for home use or were affordable to schools. I shepherded a research project with a coalition of 100 Eastern Kentucky and Southwest Virginia School teachers to give them the video, let them use them in class, and then we did a participatory research project on how teachers could use video in the classroom to facilitate hands-on work and cultural work.

So that was the first thing I did. That led to brokering a bunch of residencies with artists, but still I didn’t consider myself an artist. Really it wasn’t until it came to Southeast and we worked on that first play. There was a lot of mediating between the playwright and the director and the community about what the script was going to be, and I ended up writing a bunch of scenes, interpreting a bunch of the oral histories. A lot of it was around what Jo thought was funny wasn’t what people in our community thought was funny, and we ended up having to work on some of that. I felt a real productive give-and-take. Out of that first play and hearing some of the things that I’d put together onstage, I thought, “Well, I’m going to go to Hindman, to the Appalachian Writers’ Workshop, and I’m going to take a novel class.”

I think the other thing was that between the opioid crisis and the impact it was having on people and being involved in a citizen’s response to protect some communities that were suffering a lot of damage to their water and actual structures, actual houses and homes as a result of strip mining, and using the fact that that community was near the highest point in Kentucky as a way to protect the land around their houses, I got very interested in the children of activists and the children of people in addiction. Combine those two attributes of life into one character, and then that’s where Dawn Jewell was born.

I went to Hindman in 2006, and my first novel, “Trampoline,” came out in 2015. So that’s how I became an overnight sensation at the age of 51.

Pier Carlo: How have you handled politics throughout your career? Do you welcome or prevent politics from entering your artmaking and the discussions around it?

Robert: I think that I am as involved in just thinking about organizing and responding to political stuff and being a citizen and standing in alliance with people who are fighting for what’s right. I think early on I heard somewhere that you can’t do fiction effectively about environmental issues or about political stuff because it’ll just become a polemic. It’s interesting, being a writer, because those are the people I knew: people who were involved in things. I didn’t want to shy away from it.

I think that with “Trampoline,” a solution that I came up with was like, well, we’ll see this through the eyes of a teenager. She’s not a teenager anymore when she’s telling the story, but she’s remembering how it hit her when she was 15. The point of view gives you a way to be seen as not quite as on one side maybe. The novel itself becomes about, “Well, what do I think about all this stuff?”

The thing is things have become so divided and people are so doctrinaire, It’s hard to create meditative spaces where people meditate on the extremely complicated issues of the day. Even to ask questions about things is to be on one side or the other. To criticize anything anybody’s doing is to say, “Oh, you’re not on our side.” It’s definitely impacted our theater work.

Pier Carlo: How so?

Robert: Well, it’s just difficult to get people to come out and think about things together. It’s like they don’t want to be perceived as being on the wrong side, based on whatever side they perceive themselves to be on. With the theater work, everybody should be able to see themselves in one character. That was always kind of a byword. And that there wasn’t any kind of party line.

But it’s become harder and harder, particularly as people’s existence has become more and more threatened. The existential threat in particular. The existential threat to people of color, of course, has been present since the beginning and is ongoing, and the existential threat to LGBTQ people, the same, but has even intensified in the last five or six years. And so it becomes harder just to be a go-along, get-along person, to be like, “Well, let’s look at both sides.”

It’s gotten a lot more complicated, particularly when government agencies are getting involved in making it illegal to talk about history, to talk about the situations that living people are living through, making it illegal for teachers to bring it up. It’s not good. It’s bad. It’s bad for people’s health, it’s bad for intellectual life in the community. It’s just bad for decision-making in a democracy that we’re not getting to think about things in a full way.

Pier Carlo: Well, Robert, I have to tell you, I thought the interview was going to be, “Well, all this work I’ve done, this theater work I’ve done, has brought the community together, and everything’s getting better.” But this hits hard. How do you keep going?

Robert: It’s difficult. I think the thing is that you’ve got to think it’s just a particularly rough moment. I think that it becomes even more important to hold that space where people can come and talk about things. I think that regardless of how the work is perceived, you do the work in the way that you think is good for people and good for the community. You don’t burn bridges; you keep talking to people; you keep trying to understand where people are coming from; you don’t demonize people; and you keep making work. The people who are in the most vulnerable places need to see people sticking together and doing stuff.

I think the other thing is, again, not to be polemical, not to be so doctrinaire that you can’t find room for other points of view in what you’re doing. That holding space is more important now than ever. I think the thing for me is, you study American history and see that these spaces have always been difficult to hold and hard-won and demonized when they’re effective and belittled when they’re not.

Pier Carlo: Sometimes even bombed.

Robert: Yeah. This is the work, not just being interested in doing it when it’s easier.

We just had a great project. The work that we just finished was about a lot of things, but primarily destigmatizing mental health and what are people doing to take care of their heads in this crazy time. The play we’d done before was pretty explicitly about … it was a reflection on COVID-denying, reflection on the Black Lives Matters moment. It was pretty on-the-nose about the divisions, and so we wanted to do something a little more unifying, something that nobody’s going to feel attacked.

But of course mental health is super-stigmatized. It’s a corollary to the stigmatization of people in addiction. A couple of our later plays were about that. We did one about needle exchanges and harm reduction and how to resist dehumanizing people in addiction.

At this point [chuckling], everything can be a cause for a fight, but I think that continuing to do the work for the community to continue to have a place to go to create stuff together, it’s a lot to feel good about. My perception — and I’m less in the community on the day-to-day now since I retired from my community college job —is there are a lot of people that just get tired of fighting with each other about stuff. And I do think in small communities, there’s a certain amount of, there’s what you post on Facebook and then there’s how you deal with people when you see them in real life. People aren’t quite so full of piss and vinegar when you see them face to face.

Pier Carlo: How do you think your community views art now? I watched a really beautiful TEDx talk that you gave about art. It made me think about how many Americans think of art as being inherently elitist. You brought up the fact that the greatest art philanthropists in this country were the Sacklers, who decimated so many communities in Appalachia. So in a way, people were right to be wary of elite art.

Truly, what role do you think art should have in a smaller rural community? You talked about holding space, but how else can it be truly useful to a smaller community?

Robert: Well for me, part of it is that I cut my teeth at an arts organization which was nationally known, tons of Ford money, tons of national Endowment for the Arts money, lots of Kentucky Arts Council money. But Kentucky Arts Council … Appalshop had to fight to make the distribution of state arts money more equitable for rural organizations. They were involved in helping to win for their own organization, a category which then enabled other rural organizations to at least be able to get substantial funding. That’s been a thing that rural arts organizations have had to work for politically.

Pier Carlo: You mean at the time, even the state of Kentucky was steering the money towards bigger towns and not rural communities?

Robert: Oh, yeah. And NEA the same. Someone had to make the folk-and-traditional-arts programs a reality at NEA, within the arts community or at least the community of arts organizations and the people who are doing the hard work of making sure there is public-art funding and what does private art funding look like. This has been part of the work for a long time. I think this is why it was so formative for me to be at 1) an organization of artists, 2) a rural organization of artists and 3) an artist organization that understood, at the deepest possible level, community organizing and activism. Because that was the subject of their films and their other work. This idea that these are things in the past that have been won and they have to be held and that is the kind of place of rural people as creative people … .

Of course, I grew up in that setting, in that I was way biased towards what came out of the people: the forms, the music, the storytelling, visual-art traditions, which of course, if you spend any time thinking about the history of art and the history of music, were the wellsprings for all the rest of it. A lot of what the cities provided were markets and scholars to talk about why things were important, and they just provided gathering places for artists to see what one another was doing.

Pier Carlo: And to influence one another, right?

Robert: Yeah. If you look at what comes from cities, if you actually look at the art, so much of it is influenced by experiences that the artists have had not in that city. Or the take of the artist is based on being an outsider in the city. Of course, all that is political in terms how the community sees art. We’re not going to get anywhere, trying to act like it isn’t elitist in the minds of a lot of people, because it is. It’s one of the primary accoutrements that uppity people use to show that they’re better than other people. It’s like they’ve got art at their house, or they support the opera.

I think that, for me and in the work I’ve done in the community with other people creating stuff, there’s a certain amount of focus on the truth of the story you want to tell, focus on the beauty of the song you want to sing or that you want to play. Own the quality of what you have. Because the other thing is — this goes back to reading books about yourself in college class and Appalachian studies — you have to celebrate what you are. You have to recognize your own goodness, greatness. And you also have to listen to the voices of the people who also appreciate what you’re doing. There are a lot of people out there who think that what happens here is pretty cool, pretty interesting. They’re easily drowned out.

To champion cultural production that’s not dependent on a paid audience — “This is what we’re making for ourselves. This is what we’re making because these are the stories that we want to tell,” — it’s political work. It’s economic rebellion.

I think this gets back into, why do you have to study how the system works? Because I think that capitalism has a stake in making sure that these homegrown, homemade, non-commodified modes of cultural production are belittled and marginalized because they’re not commodified. If the whole setup is about making money, then quality has to be equated with price. So then to champion cultural production that’s not dependent on a paid audience — “This is what we’re making for ourselves. This is what we’re making because these are the stories that we want to tell,” — it’s political work. It’s economic rebellion.

Pier Carlo: So what needs to change? What needs to change so that there are a thousand Appalshops in rural communities around the country?

Robert: What I would say is there are, and that’s part of it too. They might be in wildly different stages of evolution. I would pivot the question to, “Why don’t we know about all the things that are going on? Why is that getting siloed?” The reality is, not that many people know what Appalshop’s doing.

Pier Carlo: So how could we know?

Robert: Well, I don’t know. It’s hard for me to say because I know. [He laughs.] I’m in all these national organizations. I’m in the Kentucky Rural Urban Exchange; I’m in the Art of the Rural. I don’t know; just call me. [Laughs] It does come back to media. What stories are getting told, what podcasts are getting made, or that who’s getting listed to, right?

Pier Carlo: Because even in small communities, people pay a lot of money to go see the Broadway tour that’s coming through an hour drive away, but they often don’t hear about the play or the photography exhibit that’s just down the street.

Robert: Yeah, the whole thing about audience development is interesting. And it’s important. I think about a lot and do things to make sure that people see or hear or read or whatever I’m involved with.

I think that there’s a whole thing about, maximizing the people who can enjoy it, who can get ahold of it, is different than everybody seeing it. Does that make sense? If everybody in the world knew what we were doing with Higher Ground, I don’t know that it would change our audience as much as a super-effective campaign of making everyone who would care about it know about it.

Pier Carlo: Right. It’s creating real, devoted fans as opposed to creating a big lukewarm audience, it sounds to me.

Robert: Yeah.

Pier Carlo: What advice would you give to an artist who might have grown up in a rural community or is considering moving there and who’s interested in making her or his art there but is nervous about doing so, about being disconnected from the major cultural centers? What advice would you give to him about making an artistic life in a small rural community?

Robert: Generally when this comes up, I try and get them talking about what it is they want to do, what it is they want to make, what are they feeling moved to do and scope out what’s important to them. Sometimes maybe they do need to be someplace else. I think one thing that we say a lot in this business is, “You can always come back.” A lot of the best community-based workers in rural America definitely spend some time away.

The other thing is, it’s not an abstract question. If someone came and wanted to know that, I would start being like, “Well, where do you want to live? Let’s see who we know. Here are the resources. This is how I got started. Maybe you should go talk to so-and-so. I think so-and-so is doing this.” It’s just, get into the survival strategy. “Well, how much education do you have? Do you want to teach some?” It’s like you can get some adjunct, whatever. You get into the nuts and bolts of making it at first.

Pier Carlo: Look for the literal human resources.

Robert: You don’t need a hundred jobs; you just need one. But I will say that I think one of the things that is the hardest for people who move in here is they don’t always find community. I don’t know what they think. When I came to Whitesburg in 1989, everybody at Appalshop lived in the area. We all lived there, and so there was always somebody to eat lunch with, there was always somebody. Until I got my footing. And then I had different friends, friends who weren’t at Appalshop who lived in the community.

But these days in rural communities, people are coming in one day a week. There’s working from home. It is harder to have that physical shared space. Then the pandemic has made it harder for people to be together. I’m recovering from COVID right now. It’s going on a second week of just like, I haven’t seen anybody. And that’s become more normal. I think that’s a big hard thing

Pier Carlo: That’s true in the cities too, though. Isolation has become normalized.

Robert: Yeah. I’m not having those conversations as regularly, but I do think that whoever is having them, that’s a thing that needs tending to: How are you making community for people? Because what was sustaining was the community, the community of people working with you. I do think that’s a lesson from a place like Appalshop that in some ways I wonder if they don’t need to relearn themselves. Of course, we fought like cats and dogs, and it was crazy every day, but you knew who you were fighting with, and you knew that you’d come together on stuff.

October 07, 2024