Okwui Okpokwasili

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Okwui Okpokwasili is a performer, choreographer and writer who creates multidisciplinary works that center the stories and experiences of those overlooked by history, in particular Black women and girls in America and in Nigeria, from where her own parents immigrated.

Her performance work has been commissioned by such varied cultural institutions as the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Danspace Project in New York City and the 10th Annual Berlin Biennale, and she has performed on stages and in institutions all over the world. She has received some of this country’s most prestigious cultural accolades, including a Doris Duke Award and an Alpert Award, and in 2018 she earned a “genius” grant from the MacArthur Foundation, which cited her ability to “mesmerize audiences with her shape-shifting character play, sinuous grace, and rich, hypnotic voice.”

Speaking to Pier Carlo Talenti and Rob Kramer from her home in Brooklyn, Okwui describes the grief and longing that she, a profoundly collaborative artist, has experienced during the isolation of the pandemic. She also makes the case that the institutions that deserve the most support now and henceforth are those that, like she, place collaboration and inquiry at the heart of their work and ethos.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- It certainly feels like our country is going through a period of great change. What huge changes in the arts or in dance would you like to see occur in the near future?

- You said some of the spaces you work with are already doing the work, being more welcoming. Can you give us some examples?

- How did the events of 2020 most affect your professional life?

- What did you learn about your own practice when you were forced to go, as you said, into your own corner and so far away from the regular way that you work?

- What would you tell an artist such as yourself who was working in or collaborating with an institution that was a little bit more calcified than Danspace Project. How would you tell them to try to encourage change in such an institution?

- Is there a project you’re especially excited to work on in 2021?

Rob Kramer: Today’s a historic day in the United States. A new President’s being sworn into office, as well as the first female and woman-of-color Vice President. So it certainly feels like our country is going through a period of great change.

What huge changes in the arts or in dance would you like to see occur in the near future?

Okwui Okpokwasili: In the near future, I would just like to see these art spaces, dance spaces, performance spaces — a lot of the work I do is interdisciplinary — I’d like to see these places given more support. I’d like to see these spaces given more support from cities and states in recognition of how these spaces support and, I think, nourish communities.

I think that a lot of these spaces have been having conversations that the general public is now having. They have been dealing and thinking about how to make their spaces more welcome. How do we invite people that might not necessarily think that they have a place here? How do we reach out? How do we build richer and deeper conversations? How do we build longer relationships with the community that’s here and with communities that we haven’t accessed?

I think particularly in New York, in Downtown New York, in some of the institutions that I have worked with, they’re thinking, “OK, we’re in Manhattan. How are we reaching out and connecting to organizations, dancers in the Bronx, in Queens? How are we making space for folks who are disabled, deaf? How are we making spaces? How are we thinking about the fact that we are on occupied indigenous land?”

A lot of the spaces that I have been in have already been doing a lot of what I think the nation is recognizing needs to be done, whether it’s to atone, to account for past harms and grievances. And there’s a lot to learn from them.

I think that a lot of the spaces that I have been in have already been doing a lot of what I think the nation is recognizing needs to be done, whether it’s to atone, to account for past harms and grievances. And there’s a lot to learn from them.

So how do we support them, sustain them, particularly now that they’re suffering because of the pandemic, and recognize that they are the leaders in nourishing and healing and building healthy communities?

Pier Carlo Talenti: You said some of the spaces you work with are already doing the work, being more welcoming. Can you give us some examples?

Okwui: There are places like Danspace Project. They have typically occupied a space in St. Mark’s Church.

One thing that’s particularly interesting or, I think, notable about Danspace Project is that the chief curator/executive director has been doing something called a Platform Series, which is a series that is an exhibition that unfolds over the course of, say, five to six weeks. They collaborate, co-curate with an artist. Working with the artist, they investigate a particular question or inquiry that the artist is interested in engaging.

There have been several really incredible inquiries, one of which was “Lost and Found,” where folks were thinking about, “Who are some of the artists that we lost to the AIDS crisis? What was the work they were doing then? Can you imagine the work that they may have been doing now?” They brought in artists to in some way sometimes re-inhabit the work and to sometimes reimagine work. There was a particular Platform around the history of the church, the history of the church in performance, particularly in New York. That’s when they did the excavation of the various enslaved people who built the church.

There are things that are happening like that that are pretty innovative. An institution that suggests, “OK, it’s not just about some kind of decision that we make unilaterally to give you resources, but how are we working with artists to even think about how the resources should be allocated? What are some of the pressing questions and concerns in the community that we need to investigate?”

Rob: Let me ask you a looking-back question. How did the events of 2020 most affect your professional life?

Okwui: Well, I mean, it changed everything in that it stopped everything. Everything stopped.

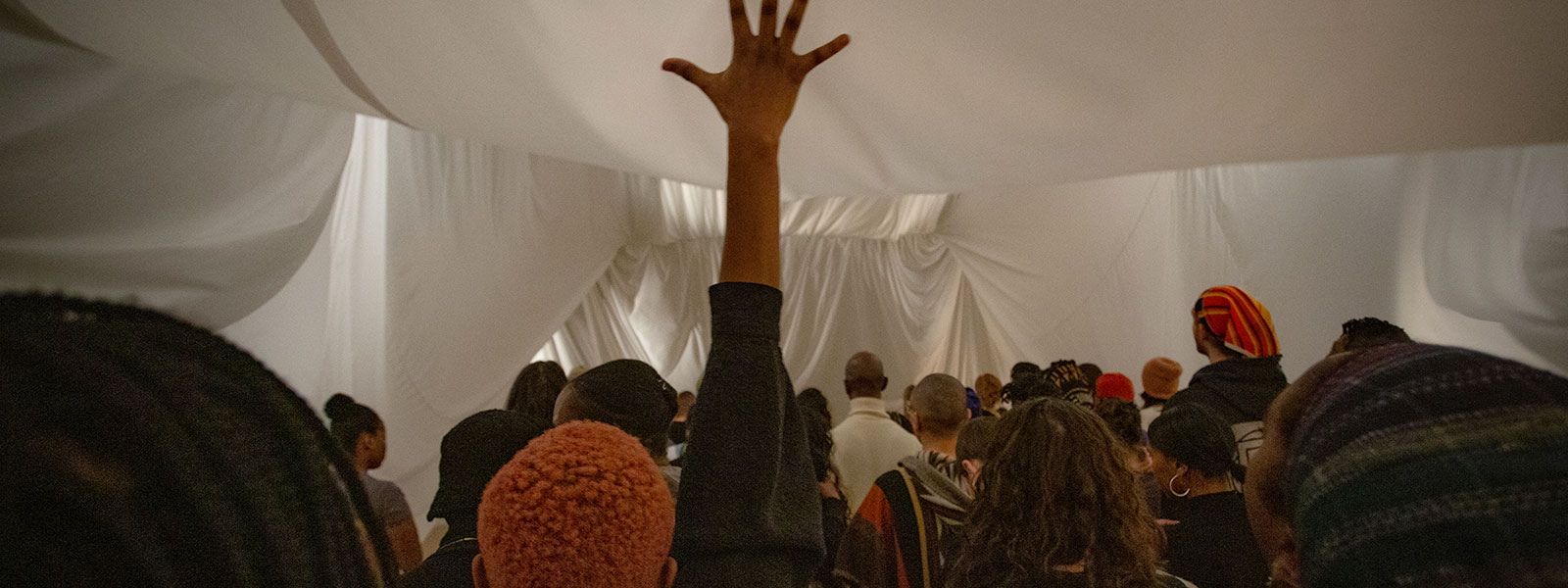

I had been building a practice around creating an improvisational chorus with the public along with artists, a select group of artists who would practice creating sonic structures, almost containers for improvisation, while doing a slow walk in an enclosed space. And we would build this sonic web, this fabric around a question of, “What do you carry, and how in turn does that carry you?”

But what it required was engaging with strangers in close proximity, singing out, screaming out, shouting out with each other, and in an enclosed space, being very close. We had been doing that practice, and that stopped. And there was a sense of...

I feel like a lot of what I do is about proximity, is about engaging strangers closely, sometimes uncomfortably, but really trying to traverse that terrain between skin, be in that space, that exchange space. So all of that stopped.

But what was interesting was that obviously with the pandemic we all had to retreat to our corners in order to actually protect each other. So actually we’re in a pandemic that suggested that the things that I had been really concerned about and thought were necessary for a restorative space of mutuality can actually kill you.

Having to retreat like that, having to go back, having to separate from each other does makes it very clear how much that space is necessary to our survival, right? We need each other. We need that exchange space. We need to be next to each other. We need to link arms, mingle breath.

I don’t know. I guess in a way having to retreat like that, having to go back, having to separate from each other does makes it very clear how much that space is necessary to our survival, right? We need each other. We need that exchange space. We need to be next to each other. We need to link arms, mingle breath.

What it did is it left me feeling quite bereft for a while. Yes, I’ve had to retreat and try to see if I can make things outside of the live space. I’m really trying to explore, what is the digital space? What’s the power of the visual and the virtual? How do I have to rethink my ideas around practice, my concern about practice, and rejigger it to really think so much more about the end result than the product? That was also complicated.

But the missing of that — the breath intermingling and the porous space, the charged space between our porousness, our mutual porousness — that missing continues.

Pier Carlo: What did you learn about your own practice when you were forced to go, as you said, into your own corner and so far away from the regular way that you work?

Okwui: I just learned that my practice is so deeply connected to other people.

Pier Carlo: Were you able to create digital, remote projects?

Okwui: Yeah, we did, we did. Yes, yes. But I think that, again, it’s sort of like instead of working with people, I had to think about the air. I had to go to the roof. I had to go to the fire escape, have an exchange with sky, dance to traffic. That space has opened up for me again.

I spent some time many years ago in Japan. I was at something called the Body Weather Farm. Min Tanaka and his company, many, many years ago started a farm outside of Tokyo where people would farm but they would also dance. You would dance in streams, you would climb trees, you would employ some of the positions that the body was in to dig out potatoes in some of the dance. It was just a way of really connecting, just really being in relationship to the world around you. Feeling the weight of things.

For me, I was feeling how the earth was holding me, or if I leaned against a tree, what parts of me … maybe my trunk against a tree trunk is secure but then my head can go wild. Or my hands are like smoke, floating away from that trunk.

So I think in the age of the pandemic, I’ve had to reinvestigate all of the other things that support me. Sometimes maybe it’s the weight of the banister.

Pier Carlo: What would you tell an artist such as yourself who was working in or collaborating with in an institution that was a little bit more calcified than Danspace Project, that wasn’t quite approaching the world in a way you envision progressive institutions doing. How would you tell them to try to encourage change in such an institution?

Okwui: It’s such a good question, because I honestly am not sure that I know.

Pier Carlo: So you’ve always found very welcoming and open spaces?

Okwui: Yes, I think so! I think calcified institutions never supported me.

Pier Carlo: [Laughing] Congratulations!

Okwui: I guess I have always worked in some way mostly with institutions that are constantly critiquing how their institution is working. Or they’re institutions that were started and led by artists, say in the ’60s or ’70s, institutions that weren’t there for the perpetuation of the institution but to keep making a space for art practice. Movement Research, for instance, something that was started by artists and doesn’t even produce. It’s only interested in process and making space for process and thinking. So I think a lot of those movements are the ones that I engage with.

But what would I tell an artist who might be of my ilk or my kin who is working in a calcified institution? It would be hard for me to know. Even though I think in this moment it might be easier for those artists to have deeper conversations with these institutions, because these institutions are rethinking. They’re getting pushback about a lack of representation, a lack of diversity, particularly in the administrative space.

Rob: Is there a project you’re especially excited to work on in 2021?

Okwui: I actually am revisiting a project. It’s a 50-minute-long song that I made that is a reference to the 1929 Women’s War in Southeastern Nigeria, where women were protesting colonial practices that they felt were a kind of existential threat to their ways of life. And they in fact were. I mean, colonialism was and is an existential threat to cultures. So I made this 50-minute-long song, which is a practice in duration, thinking about the grievance of these women but also trying to open up a portal that perhaps I can reach these women. So it’s also a kind of extension of my grief around this disconnection and maybe my inability to access these women.

I’ve been working on that, and I’m excited about that. And I’m going to be performing it at the New Museum in February as part of a show called “Grief and Grievance.” It’s curated posthumously by my namesake Okwui Enwezor, an incredible curator who passed away two years ago. In his practices of curation he was really undoing this idea of Europe and the West as central to artmaking and creation. He really started to reshape how we were looking and thinking about art practice, artmaking, particularly contemporary art. And he was really building a platform to deeply interrogate and view contemporary art from the Americas, from Africa, Asia.

So we’ve been working a lot on music and sound.

Pier Carlo: And is “we” your collaborator, your husband, Peter Born?

Okwui: My collaborator, my husband, yes, yes. Together we’ve been making lots of songs and sounds.

There’s the longing part. The longing for other bodies can come in with a vengeance in ways that are unexpected. I saw somebody I hadn’t seen in a while in person, and we held each other. That kind of thing is so ... . What’s going to happen when we all can finally be with each other again, we’re all vaccinated, we’ve achieved herd immunity, and we’ve taken off our masks and we’re touching each other? [Laughing] I mean, the paroxysms of joy and grief and pleasure!

I guess maybe my performance is always trying to suggest — it’s obvious now — that our bodies are filled with stuff. What happens when we access it? What happens when we make this space to access it?

Again, the body. What are our bodies going to do with all of that stuff? I guess maybe my performance is always trying to suggest — it’s obvious now — that our bodies are filled with stuff. What happens when we access it? What happens when we make this space to access it?

When we think about all of the Black folk who have been oppressed or violated by police, who are constantly seen as monstrous, as violent. And so the State acts that way to them. And I feel like you’re not just talking about what happens in your lifetime but all of the lifetimes before you that have been holding onto that experience of violence, that memory of violence. For me, it’s always like, “How do we open up and access that?” But it’s true, I still don’t always know what to do with it.

February 8, 2021