Chip Thomas

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Chip Thomas moved to the Navajo Nation in Northern Arizona in 1987 to work as a physician in a community with limited healthcare and thus repay a National Health Services Corps scholarship. The plan was to stay there four years. Thirty-four years later, Chip Thomas is not only still living and working as a physician in the Navajo or Diné Nation; he has also become an artist beloved by his community and increasingly by admirers from all over the world.

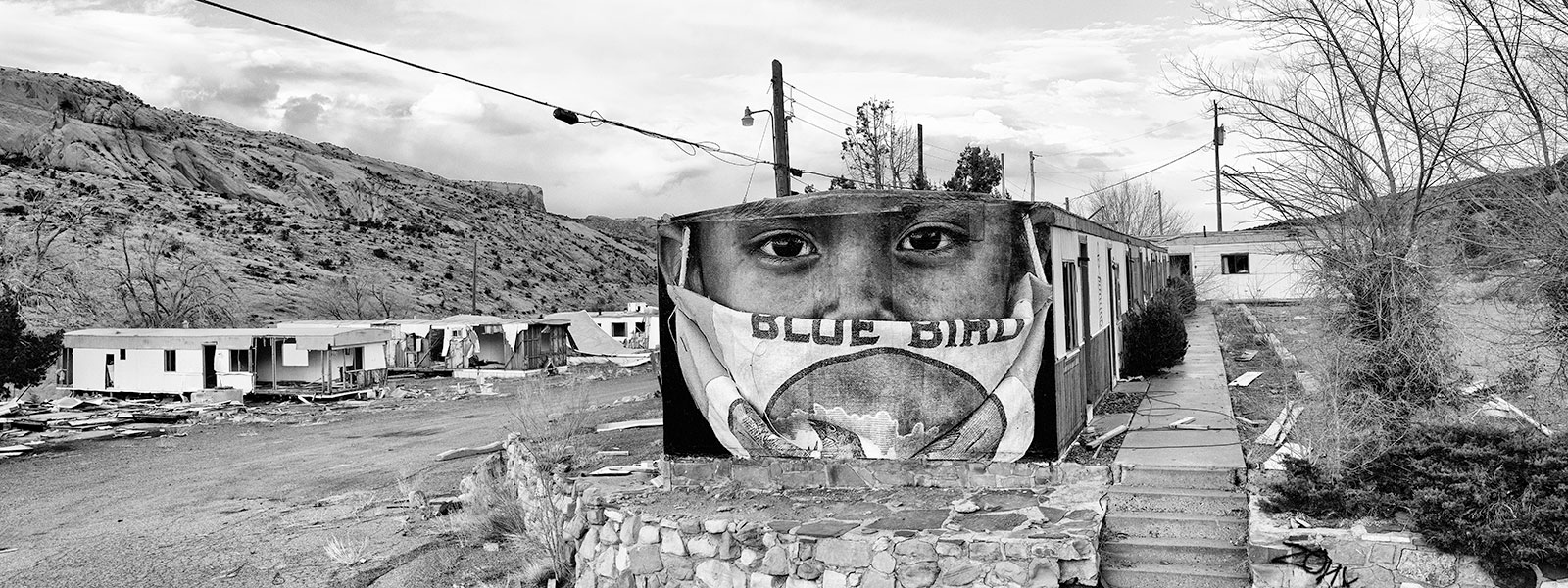

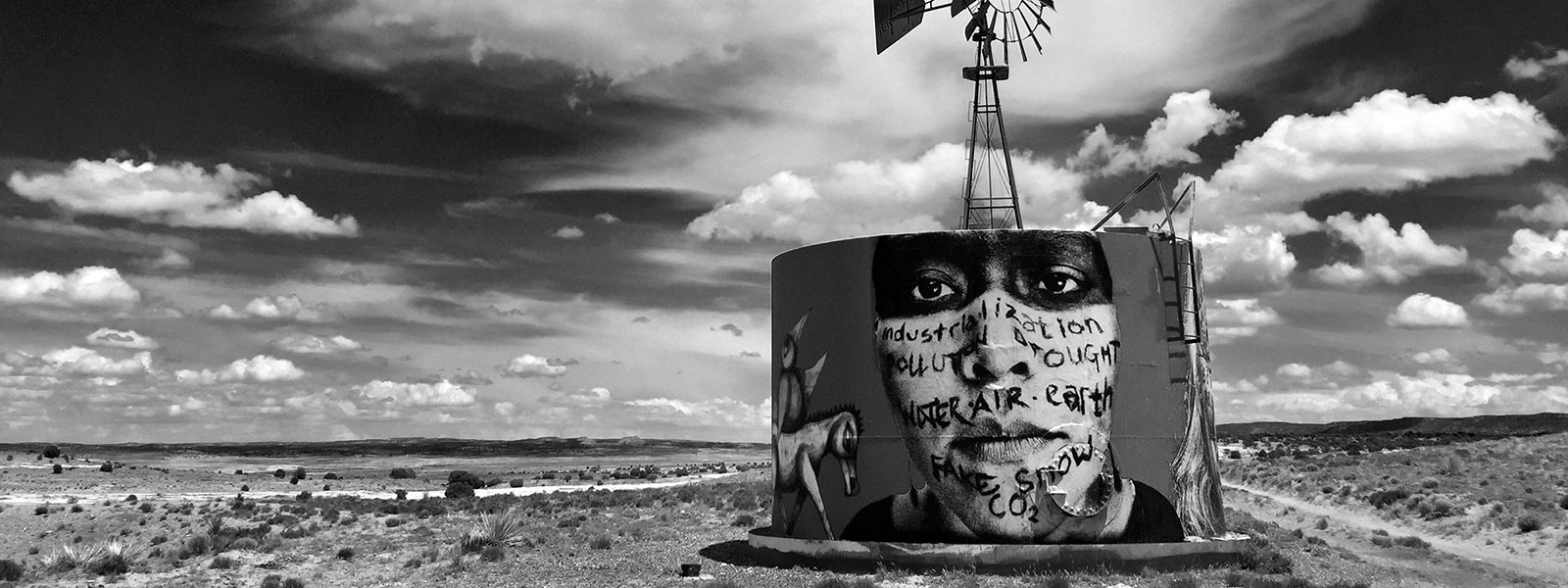

Since 2009 Chip, an avid photographer since his teens, has been printing out large-scale enlargements of his photos of his neighbors and community and affixing them to structures throughout the Diné Nation, reflecting the beauty and stories of the people and their culture back to themselves. Sometimes the murals also tackle the many social issues and environmental issues, such as the sickening effects of uranium mining in the 20th century, that have challenged the Diné for generations. During the pandemic, Chip created murals to share vital health information with his community, which was disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

In this interview with Rob Kramer and Pier Carlo Talenti, Chip recounts how he earned his neighbors’ trust, first as a physician and later as an artist, and harnessed his combined skills to serve and improve the community’s overall wellness.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- How have you navigated the last year? Where have you found the resilience to keep you going?

- When you first arrived at the Navajo Nation, I’m sure you were seen as an authority, because you’re an M.D., but how long did it take for you to be trusted as an artist? How did you negotiate that relationship with the community, and did you make any mistakes along the way?

- With the impacts you’ve made both as a physician and an artist in the community, someone might say you’re a change agent or you’re a leader or you’re an artist leader. What role do you see yourself playing in your community these days?

- From your experience and also what you’re hearing from colleagues, what could be changed or reinvented in order to make sure that communities have access to art and that, as you call it, their overall wellness could be improved through art?

- Let’s say a young artist is listening to this and wants to do the kind of community-practice work that you’re doing, maybe go into a rural community and be of service through their art. Is there one piece of crucial advice you would give this artist?

Rob Kramer: How have you navigated the last year? Where have you found the resilience to keep you going?

Chip Thomas: It’s an ongoing process. The pandemic is still with us. Just Thursday and Friday of this week, we got seven positive tests back for coronavirus after not having had any — or maybe one or two — over the past, say, five weeks. There were some people who attended a super-spreader event, which I think was a religious event locally, so we were getting the virus type to see which strain we’re dealing with. The point being, the pandemic is still with us. I’m still navigating all of this.

But again the thing that is saving me is the opportunity to go out and create art. Like right now, as I look outside, I just looked at my thermometer, and it’s 70 degrees. I live at 6,500 feet. It snows in the winter. It’s not unusual to get lows in the single digits here. It’s been cold pretty much for most of the winter. Just having an opportunity to go outside and work. Exercise helps me. I cycle still, generating endorphins and enkephalins.

I think the focus of my art, really, is using it as a tool to build community, and within community there are opportunities to process all sorts of stuff. For example the UN World Health Organization got in touch with me within the past six months, saying they are aware of the work that I’m doing and the impact it appears to be having. The World Health Organization is also aware that parallel with the pandemic there is an escalating mental-health pandemic or crisis, with more suicides, eating disorders, depression. Maybe even some of the gun violence that is happening now is a result of things that have happened during the pandemic with the amazing amount of loss, jobs, lives and so on.

So “The Painted Desert Project,” which I do, is one of five community-based art projects that the UN is going to work with over 2021 to come up with an art-focused response to community grieving and healing. After I finish this interview, I’ll be driving to a really beautiful canyon site where there is an abandoned motel that’s been stripped of its materials. It’s been trashed, but we’re going to lead an effort of people coming together to clean it up and maybe use it as a site for storytelling of the impact of the pandemic on the community but also as an opportunity for healing and coming together.

A lot of times I will say in talking with people that the clinic work is all about trying to create an environment of wellness within the individual to restore them to optimal health. But the placing of what I consider positive images in the community is trying to create an environment of wellness in the community and how people are feeling about themselves, about community.

So being in community, sharing with people, making art is what is helping me get through this. It’s really a counterbalance to the intensity of the work that I do in the clinic. A lot of times I will say in talking with people that the clinic work is all about trying to create an environment of wellness within the individual to restore them to optimal health. But the placing of what I consider positive images in the community is trying to create an environment of wellness in the community and how people are feeling about themselves, about community.

Pier Carlo Talenti: When you first arrived at the Navajo Nation, I’m sure you were seen as an authority, because you’re an M.D., but how long did it take for you to be trusted as an artist? You take such intimate photos, I think, and then put them up in very public spaces, which is a scary thing to do for many people. How did you negotiate that relationship with the community, and did you make any mistakes along the way?

Chip: Yes. [He laughs.] Yes, mistakes have been made.

I’m doing this work in a community that doesn’t have, say, the disposal income for there to be a lot of murals along the roadside. At the time I started doing my wheat-pasting project, I wasn’t necessarily putting work up in places where there was already street art. It’s a complicated history of photography with Indigenous nations and how they are represented and oftentimes idealized and made to seem static and represented in a way that doesn’t give the impression that Native people are still here.

But being influenced by the visual storytelling of Eugene Richards, Eugene Smith, basically the Magnum group of photographers, I have always been about trying to get in there and go deep and to hear those stories and use the imagery as an opportunity hopefully for people to learn more about the community and to hear some of those stories.

The trust-building just takes time. There’s an expression within the community that I learned shortly after I came that unless you’ve been around for a couple of years, people don’t really take you into their trust. It’s really about them observing you and seeing if your words are consistent with your actions. It has been a funny thing, because I’ve worked with a number of people in the clinic over the years, and certainly there are other physicians whose interpersonal skills of communication are more effective than mine [he chuckles], and I always felt that I wasn’t as well-liked as them.

Having been here for so long, people appreciate my commitment. One of the things that I hear from patients that I appreciate is that they feel like I listen to them and that I care, which makes sense, because the art project is really coming from a place of love. I would like to think that when I engage people, engage community, I’m coming from a place of love. By the same token, I would hope my medical practice is coming from a place of love. I think people pick up on that. Like I said, they see the images. The project of putting pictures along the roadside is now primarily a conversation with the Diné People.

It’s awesome that people from all over the world traveling to tourist spots across and around the reservation see the work and are intrigued by it, but my primary audience and people I’m responsible to are people on the reservation.

For example, when I first started doing the work and wasn’t really engaged in the community, I thought, “OK, how can I do this objectively so that no one group feels excluded here on the reservation?” And it occurred to me that there are three primary spiritual practices on the reservation. There are people who are Christians; there are people who are traditionalists who still take part in traditional ceremonies and do things like sweats; and then there’s the Native American Church, which is the group of people who go into teepees for a night and have a prayer circle to bring community support to someone who is called the patient. But it also involves the ingestion of peyote.

I thought that by representing or having imagery from people in those communities, it would make the work more acceptable. So I put a photograph of a friend who had a peyote bud in his hand. He was showing it to me, so I photographed the palm of his hand and then made kind of a mandala out of his hands with the peyote bud and pasted that on the side of a roadside stand, not knowing that the owner was a fundamentalist Christian who had absolutely no tolerance for the Native American Church, who took the piece down within 24 hours and then found me and berated me. This was at the time when no one knew who was putting pictures up.

There was another example. There’s a developer in Scottsdale who wants to put a development on the East rim of the Grand Canyon, which is on Navajo Diné land. He wants to put in a one-mile tram to take approximately 10,000 people a day down to a site in the Grand Canyon at the confluence of the Little Colorado River and the Colorado River to make it a little resort area on land that at the top of the Canyon has no development, is a community on the reservation that has an unemployment rate of probably around 60%. There are just no jobs in that community. But the development itself is not sustainable in terms of taking that many people to the site, which by the way, is a site that’s sacred to all of the Pueblo tribes in this region. It’s also the area where the Zuni, the Hopi, would do their treks to get salt once a year.

The more traditional people were opposed to this development, and I realized, “Hey, I have a skillset that can amplify voices advocating for positive change within the community.” So I approached the traditionalists and said, “Would you like me to put some posters along the roadsides speaking to how you’re feeling about this issue?” I worked with a couple matriarchs from the community to make imagery, which we put up.

There were some other people from the community who came to me and said, “Hey, look, there are no jobs here. This is not your community. Why don’t you go paste your own house?” And then they buffed or painted over everything.

So yeah, I’ve made mistakes along the way. What I learned pretty early on is that the subjects that are safe are sheep, because there’s an expression here on the Navajo Nation that sheep are life. People used to gauge their wealth by the size of their sheep and goat flocks, but then they would shear the sheep, spin and dye the wool and make these beautiful rugs which are still being made. When they butcher sheep, they eat every part of the animal. They have a serious relationship with their sheep.

So I learned early on that putting up pictures of sheep is safe. Putting up pictures of code talkers, the guys in World War II who used their own language to help beat Japan in World War II. The Navajo code was the only code the Japanese didn’t crack in World War II. So the code talkers. There’s only one or two of them left now. They’re in their nineties. Pictures of code talkers are safe. People here on the res love them.

There was one guy who told me when he’s driving around in his truck with his grandma or great-grandma, anytime she sees the pictures of sheep, she just gets a big smile on her face and starts laughing. So that’s my metric for success, happy grandmas.

Over time — I’ve been doing this for 12 years now — it’s nice when people approach me and say, “Hey, will you take a picture of my grandma?” A lot of times people ask me, “So what’s the impact of this project on the people of the reservation?” I don’t have the metrics really to know that. I get occasional messages on social media. There was one guy who told me when he’s driving around in his truck with his grandma or great-grandma, anytime she sees the pictures of sheep, she just gets a big smile on her face and starts laughing. So that’s my metric for success, happy grandmas.

Rob: With the impacts you’ve made both as a physician and an artist in the community, someone might say you’re a change agent or you’re a leader or you’re an artist leader. What role do you see yourself playing in your community these days?

Chip: Will you ask me that question again? I just got a text from someone I called medicine in for, and I missed the question.

Rob: OK, no problem. Given your work as a physician and as an artist in this community, how do you view yourself and your role? How would you label yourself? What do you do in the community?

Chip: Oh, that’s a good question. How do I label myself? Everyone in the community knows me first and foremost as a doctor, a doctor they can trust, someone they want to see by and large. That’s why I am here. Yes, I do art in the community and I try to use it as a tool to build community, but I don’t necessarily put that first and foremost when I’m … .

It’s an interesting thing, because I went to Wake Forest and then I went to Meharry Medical College in Nashville, TN, and none of that came easily. I wasn’t a scholarship student, in that I had to work for everything and just spent a lot of time studying. Art, on the other hand, is something that is all self-taught. It’s really me expressing what I’m feeling, speaking from my heart.

Because of my medical training and because that’s the work I’ve done, everyone here knows me as a doctor. In truth, even though I worked in my home darkroom for 22 years, I never really thought of myself as an artist. It wasn’t until I started going out into the community and playing with the architecture of walls and buildings that I started thinking of myself as an artist. When I started my art project in 2009, I had never heard of community practice. [Laughing] I didn’t go to art school.

OK, I’m going to take a step back further. I mentioned I’m from North Carolina. In ’68, the Raleigh public school system was desegregated, and that’s when busing started. Once kids got to the school they were going, there was a lot of violence happening. My mom was a schoolteacher in the public school system, and this was ’68, ’69. There was a lot going on in the country at that time. King was assassinated in 1968. So my parents were concerned about the amount of violence in the public school system. They were looking at sending me to a military institute in North Carolina or Virginia, which I really didn’t want to do.

But a fortuitous thing happened where my parents in the summer of ’69, the summer of Woodstock, took a cruise with my grandma for three weeks and my father learned of this Quaker camp up in the mountains of North Carolina where they do rafting in the river, horseback-riding, camping, just all of the things I love doing. I’d never been horseback-riding, but … .

So I got to go into this small Quaker community in Celo in 1969, and the four other guys in my tent were going to this school called the Arthur Morgan School, which was an alternative Quaker boarding junior high school with 24 kids. You know the history of Black Mountain College? This school was set up like that, in that it was a work-learning experience. The first time I went into a darkroom, I was 13 years old at the school. That summer I got my first camera, started shooting black-and-white film at that time.

The experience of making decisions by consensus and living, working, creating together was instilled in me at a young age. ... I think if there’s any agent-of-change work, it just comes from being a part of community and having an open conversation with that community.

The experience of making decisions by consensus and living, working, creating together was instilled in me at a young age. In terms of being an agent of change in the community, that junior-high Quaker school experience was all about building community. Every spring, we would breakout into small groups — and again, there were only 24 students in the school — and do field trips to different parts of the country. We would go to the Black community where the Gullah and Geechees were; there was actually a small Black Quaker community there. We would just volunteer and do community service in that community for the two weeks we were there.

That type of grounding and community has stuck with me and led me to being where I am now for 35 years, doing longitudinal work. That in and of itself, to have a physician in the community for this long, is becoming rare. I think if there’s any agent-of-change work, it just comes from being a part of community and having an open conversation with that community. When I say open, it’s one that everyone can see.

Pier Carlo: At Art Restart we like to talk about systems that need to be reinvented so that it is easier for artists to make a living at their art and also to bring their arts to their communities.

From your experience and also what you’re hearing from colleagues, what could be changed or reinvented in order to make sure that communities have access to art and that, as you call it, their overall wellness could be improved through art?

Chip: I saw a survey maybe three or four months into the pandemic this year or 2020, and it asked people to rank in order a list of people or occupations they considered the most essential and the occupations they considered the least essential.

Pier Carlo: Uh-oh, this makes me nervous.

Chip: Yeah, you can see where this is going. To make a long story short, people in healthcare responding to the emergency of the pandemic were rated at the top.

Pier Carlo: So you’re at the top and the bottom of the list!

Chip: That’s where I am going with this! I represent both ends of the spectrum. I’m actually all about advocating for a deeper appreciation of the value of art.

I think the only way communities get that is when they see it and feel it. I don’t know that the Navajo Nation would have decided — and the Navajo Nation still hasn’t decided — to invest in an arts program, but people here appreciate the value of public art in a way that maybe they didn’t 15 years ago. There are more public art projects starting to happen on the Navajo Nation.

For this UN/WHO project I’m doing, I brought together a diverse group of people. There are seven of us on my team. We represent community organizers, art therapists, artists, activists. Half of the group is Native, actually over half. I think when people form teams to look at any type of civic engagement or even the construction of parks and buildings, it would be nice to have someone with an arts background as a part of the planning team. I think artists are great at thinking outside of the box, and maybe taking chances that people in other disciplines are less likely to do.

It just goes back to appreciating the value of art. Most countries in Europe will support artists and give them the income to make a living, but it’s really hard in a country whose emphasis is on the accumulation of capital. I think there needs to be a refocusing of our values as a country. And if it’s solely about the accumulation of capital, then yeah, we’re going to continue to destroy the planet and ruin the environment and create climate change and decimate animal populations and treat people like they don’t really matter, like we are also a commodity, and not value people’s basic rights to healthcare, education, housing. It’s a large problem. It’s a large issue.

Pier Carlo: Let’s say a young artist is listening to this and wants to do the kind of community-practice work that you’re doing, maybe go into a rural community and be of service through their art. Is there one piece of crucial advice you would give this artist?

Chip: Yeah, breathe. [He laughs.] Give it time. It really helps to come to a place and just listen, not to come in with ideas and solutions.

For example, one of the things that occurred to me: The UN asked me why my project is necessary, wanting me to, I guess, justify it. And it occurred to me that my project is not necessary. I am working in a community of people whose ancestors came to this area roughly 10,000 to 40,000 years ago (it depends on which migration one considers from the Siberian area). The people here are resilient. They have ways of adjusting to times of privation such as we’re going through now.

So it’s really not what can we bring to help them, but what can we go and patiently listen and learn from and maybe work with and build relationships around. That doesn’t happen quickly.

I’m fortunate in that I have an excuse for being here. I have my job that allows me to be in this community and to have these interactions. It would be hard if I were living off the Navajo Nation land and trying to maintain these relationships.

Pier Carlo: It also sounds like you have a deep love for the place. It sounds like you have some spiritual connection to it. You are deeply invested in the geography and the culture.

There’s something transformative just about being in a stark but beautiful place over an extended period of time. I guess I would tell a young artist to go to the desert and wait.

Chip: Yeah, no doubt. Not to get religious, but was it Moses who spent time in the desert and had a transformation? There’s something transformative just about being in a stark but beautiful place over an extended period of time.

I guess I would tell a young artist to go to the desert and wait.

April 19, 2021