Aaron McIntosh

Listen to the interview on Apple, Spotify, or your listening platform of choice. Captioned interviews are available on YouTube.

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For fiber artist Aaron McIntosh, quilting is an act of defiant documentation. Growing up in an Appalachian family with a generations-deep tradition of quilting, he learned the craft as a boy and went on to develop his own ethos and mission, studying first at the Appalachian Center for Craft in Tennessee and then earning his MFA at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

In recent years, Aaron has placed his own personal history and metaphorical body into fabric sculptures that blend his familial and cultural background with his identity as a queer Appalachian artist. His work has been exhibited in a variety of institutions, from the Houston Museum of Fine Arts and the Toledo Museum of Art to Hangaram Art Museum in Seoul. In 2015, he started the “Invasive Queer Kudzu” project, a community storytelling, archiving and art-making project focusing on queer communities, past and present, in America’s Southeast.

In this interview, Aaron, who is currently an associate professor at Concordia University in Montreal, describes why and how he claimed the South’s most notorious weed as his artistic inspiration and clears up any misconceptions about the fiber arts ever having taken a back seat to other fine arts throughout human history.

Pier Carlo Talenti: What is it specifically about fibers and textiles that make them the perfect medium for you to archive queer history?

Aaron McIntosh: This is a question that comes up a lot. Why work in textiles in general? Why work in quilts? Quilts were the first art medium and art practice that I ever encountered.

Pier Carlo: Because you come from a family of quiltmakers, is that right?

Aaron: I do. The ones that are remaining are still very much active quilters, in different ways and different capacities. In many ways their objectives are really different than mine. They’re about beautifying the home or making do with what you have. Both my families come from very lower-working-class backgrounds in southwest Virginia, in the Roanoke Valley region, and the Tri-Cities area of Northwestern Tennessee. They’re two Appalachian families, both with really different and rather rich and extensive quilting traditions.

On the Tennessee side of my family, my dad’s family, were much more improvisational quilters. I grew up around a grandmother who only lap-quilted, meaning she did all the piecework and the quilting in her lap and without a lot of fancy equipment. She didn’t use a lot of patterns and did a lot of blocky work. A go-to reference for listeners is the work of the quilts of Gee’s Bend, which many Americans know about. That’s what my grandmother Axie McIntosh’s quilts look a lot like, and the quilting tradition she’s from looked a lot like that.

On my mom’s side is a lot more order. The Virginia side, they were really into patterns. They obsessively clipped patterns from Ladies’ Home Journal and newspapers. A part of the quilting archive I’ve inherited from that side is a catalogue of a lot of those patterns.

Pier Carlo: Was it subversive or shocking to the family that there was a boy —

Aaron: A grandson who was doing this?

Pier Carlo: Yes.

Aaron: No. On my mom’s side, my great-grandfather, was a very active quilter, extremely active. I have one of his quilts. The pattern is called “Bowtie;” it’s very common across Appalachia and other parts of the U.S. He was widowed at an early age and raised the kids by himself, two daughters and one son. Quilting was kind of a release for him, as it is for many people, but it was his primary winter activity. He loved it. He was proud of it. He showed off his quilts. My understanding is that was because his father, so my great-great-grandfather, also helped his wife with quilting and so he didn’t grow up with this sort of gender paradigm for the craft. And so I didn’t inherit any of that.

My grandmother Axie — Flag Pond, TN, is where she’s from, close to the North Carolina border — was the one who put fabric in my hands and encouraged me to quilt and to sew, so I didn’t really grow up around any of those gendered associations. People asking the question like you’re asking, no one really ever asked me that growing up. As a boy child who was really effeminate and definitely chose dolls and more female- or girl-leaning toys as a kid, even though I grew up in a really strict, religious household, I didn’t have a lot of people breathing down my neck about gender norms.

I certainly have lots of friends from the region who have trauma stories — I have my own, especially in the ways in which the church would interfere with people’s natural efflorescing as queer people — but I think oddity and originality and individualism are just so prized in Appalachia that I think that is in general why queer Appalachians might just do things their own way. Normally you kind of “see” one another when you encounter each other if you’re from the region.

Pier Carlo: Could you talk about how your artmaking came to meld the landscape of the South with an examination of queer history and culture?

Aaron: Before 2015, I was mostly working on quilts, like proper quilts — not necessarily for a bed but made like a traditional quilt and might be hung on the wall — or sculptures that involve quilt-making or piecework. Beginning in 2015, I had been sculpturally working on this project about my family’s relationship to the land. We use the word decolonization a lot now, and I have a backwards-looking sighting on that work. I think I had a lot of my own questions like, “Well, whose land is this? Why is land and connection to land so important for rural people? Why has it been so important for my Appalachian family? Why is it when you ask people to index what makes home in Appalachia so special, it’s about the connection to the mountains?”

I’d easily say that’s a big part of my life too. There’s something about when I’m flying home, usually into Asheville, NC’s airport, seeing those mountains, it’s like a different neurological thing happens in my body. I do feel like I’m coming home. I wanted to explore why my family has a lot of interesting struggle related to land and land ownership and property.

My family has always relied so heavily on the land. My parents until very recently only used wood-burning stoves. They grew a lot of their own food until very recently. They’re now in their 80s, so all of these things are changing. I grew up in a family that made do with everything. Most of my extended family were growing their own food. My parents grew their own beef cattle for many years. I just wanted to explore that for myself and bring that into a quilting practice and an art practice, and at a certain point a writing practice.

And so I started taking on different elements. I made a project about firewood and growing up in the woods and growing up in the forest and made a series of trees that were made out of images of my own flesh. I made a taxidermy bear related to my mom’s side of the family, where they are all big bear hunters. I was thinking about why that tradition so important for them and yet it’s not important for me and what do I do with a lot of these family heritages that I will not continue? What does that mean and what is the burden of that? Looking at a lot of these forms, reinterpreting them in quilted or piecework or patchwork sculptures led me to also think about plants writ large.

I had a particular experience in the final weeks of my grandmother, my mom’s mom, passing away when we were tending her final garden. This is in Newcastle, VA outside of Roanoke. In that garden it had grown extremely weedy due to her ill health. I’m out in that garden with my mom and her sisters, and we’re weeding. Everyone’s just talking about these weeds and I think channeling the grief and the sorrow but also some anger. Being from a gardening family, I grew up hearing about how much people hate weeds and how it’s the thing they hate the most. And I’m just sitting there thinking, “In this time of family grieving, it was made pretty clear to me that my five-year partner should really not be around the family at that time, that that makes people uncomfortable.”

I just saw myself in those weeds as a queer person. I saw myself as someone who’s from here, a native species — usually most weeds are — and that it’s through culture that we pick and choose what is wanted and what will be discarded, and what will be cultivated. Plants are just doing their own thing, just like queer people are often doing their own thing. We are born this way, we are who we are, and then it’s culture that we usually have to contend with. The weed became an important queer metaphor for me, and so I started making weeds about my own experience.

I picked 10 of the most common weeds that I had a relationship to in the southeast and then spent time picking and discarding, and I recreated those in the kinds of materials that index my queerness. They’re the archive sources I was referring to earlier but also family cloth and things like romance novels that I used to read and get from my female relatives.

With these patchwork skins of queerness, I made these weeds. And two years into that project I started thinking, “What’s the ultimate weed in the South?” I was remembering all this pejorative language about weeds, and then, well, I had to take on kudzu.

“Invasive Queer Kudzu” series, 2024, Aaron McIntosh; Photo courtesy the artist

Pier Carlo: The great thing about kudzu is actually it has a beautiful leaf.

Aaron: It does. It’s often like the shape of a heart or a kind of crown.

Initially it was just thinking about kudzu as a weed, as an extension of a weed. I showed that work for the first time in Baltimore and had a really positive reception from other queer people and other friends, artist friends. But a common refrain was, “This is great, but if you’re going to talk about kudzu, you’ve got to get there with the mass.” The first showing I had was just really a small, polite amount. It was taking over one of these flesh trees that I had made about the work in the forest. I started thinking, “Well, how am I going to do this?”

It was at that time that I started becoming a little bit more exposed to this network of queer archives in the South. Spending a little bit of time in Baltimore early on in 2013 and '14 opened me up to this really radical idea, which is that one reason queerness in the South was so suppressed by our conservative southern state legislatures is that it’s very easy to sweep away the history of queer people in the South because there has not been that much of it added to official state histories and to official state archives. That has to do with all kinds of cultural things: the predominance of the church, the predominance of shame in small, rural, isolated religious communities.

I initially thought, “I want to do this project about archives. I want to grow this giant mass of kudzu about the history of queerness in the South.” I got more invested in that, and started visiting a lot of archives. I was making scans and taking photos, and those get translated into material by being printed onto cloth, and then those would be quilted into the shapes of kudzu leaves and then added to this growing mass of vines.

I quickly realized the limits of an archive-based project, which is that to be in a region as racially diverse as the South was to really see the absence of Black communities in these archives. The more I would see that, the more I would feel really despairing about these archives. Every archive is maintained by those who have the time, the power, the privilege and the funds to carve out time to save that material, to make it known, to keep it, to preserve it and pass it on, so these archives also speak to the power struggles and white supremacy in the South. It’s not specific to the South; it is all over North America and the globe. But it felt like I couldn’t just rely on these archives to, if you will, paint a picture or grow a kudzu vine in the way that it needed to be grown to meet the queer communities that I grew up in and know across the South.

And then the other part of that that was triggering was to see the ways in which gender is contextualized from early gay lib until roughly the early 2000s, in contrast to the way that we do and think about gender differently now as queer communities. I didn’t really want to just be showing so much of the past and not also allow a part of the gender revolutions that we’ve been through as queer communities to be in this project.

Pier Carlo: How did you respond to those challenges? You actually went out and started meeting and involving the community, is that right?

Aaron: I did, yeah. I was actively involved at that time in my last two years in Baltimore with a project called the Monument Quilt Project, which is an incredible quilt project created by good friends of mine at the time, Hannah Brancato and Rebecca Nagle. That project doesn’t continue anymore, but it was a project that was about survivors of sexual assault, sexual violence and rape, sharing their stories. With my quilting background, I was invested in that project when it was first getting off the ground. I was taking on my own interesting project that was growing towards community, and so I consulted with them. Having access to that kind of project and seeing how it worked gave me a really good footing for how I would want to do my own community contributory aspect to this work. And so it wasn’t hard to start.

I’m also a textile educator and have been for 15 years now, and so I’m used to teaching people and encouraging people to feel confident and leave their marks. My project is different [from the Monument Quilt]. I was asking people to contribute a story, something about being queer in the South, to write it on this cloth kudzu leaf with an enamel paint pen or a Sharpie marker, something that would be archival. Then those would get quilted later. I started going to community centers, to SAGE groups, queer elder communities, a lot of queer youth groups. At the encouragement of friends, I started taking it to pride events across the South.

The range of communities might be really small, or it might be really big. When we would do big Pride events in DC I would receive over 400 leaves a day. Then all those would be quilted and added to a vine. The day and the place where it was made is commemorated on that vine with a ribbon, so there’s an archiving within the project of who participated, not names, but in general locations.

It was amazing to meet the community, and people were really receptive, really enjoyed contributing to something like that. It shifted my relationship and in a lot of ways moved this project out of my entire artistic practice. My name gets attached to it, and I did originate it, and it originated in a space and time that’s very connected to my own practice, but I consider myself a project manager and a steward of these stories at this point.

Pier Carlo: Where does the vine live? I mean, it’s not always on display, right?

Aaron: No, it’s not always on display. I’m happy to say that for the last almost 18 months it’s been traveling around. Just a quick note: This project wasn’t intended to stop but had to forcibly stop because of the pandemic. I couldn’t meet people in person anymore.

Also, I ended up taking a new job. I relocated to Montreal for a job within my textile field, and so it seemed to be not a conclusion of the project in perpetuity but a time where it was going to go into a state of dormancy. There was actually a lot of self-archiving of the project in the months before I relocated to Montreal. It lives in a series of boxes that are very well-marked with the names and the places of either which archive the vine comes from or what communities a community vine was made in.

That lives in an art storage locker in Richmond, VA. It’s been shown in Boston at Northeastern University now, and it traveled from there to Missouri State University in Springfield, MO, and it’s right now at Columbia State University in Georgia. And it’s going to be going to my hometown next year, I’m excited to say, for a museum project about faith and landscape — and landscape as a kind of faith — at East Tennessee State University’s Reece Museum.

Pier Carlo: That’s fantastic. How has your quilt-making family has reacted to your artwork?

Aaron: Well, like many queer Southern people, I am various levels of “out” with my family. I’m a married queer person, so my immediate family know a lot about that, about me, and love my husband and all that stuff.

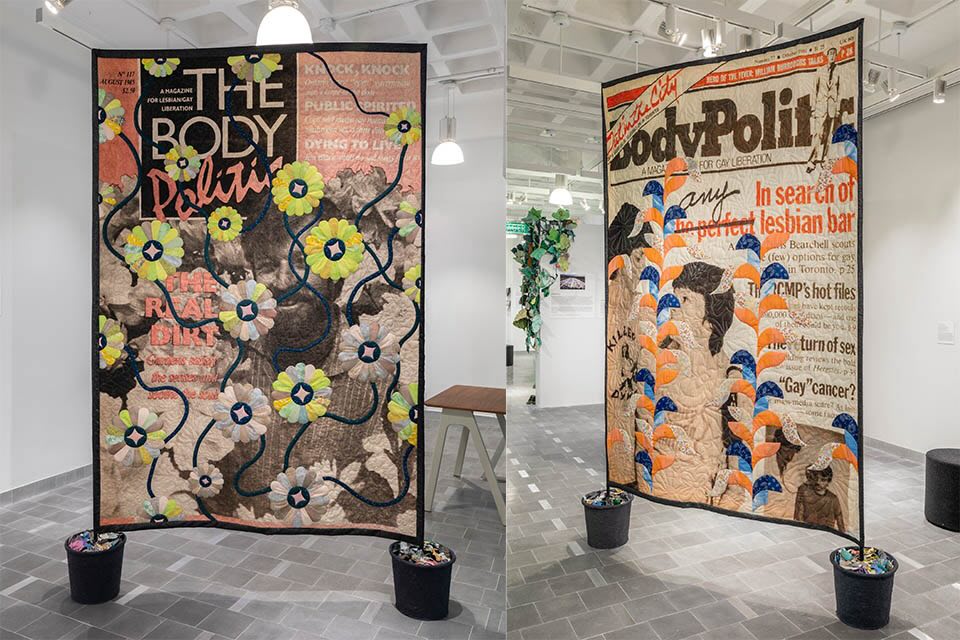

“Entanglements (Flowers at the Border)” series, 2024, Aaron McIntosh; Photos courtesy the artist

Pier Carlo: But it seems like the community at large might soon know more since there’s going to be a museum display in your hometown.

Aaron: Yeah. I mean, I’m 40 years old. I’m not really afraid to encounter that at all. Something that’s worth noting is, I always tell people, in a weird way deciding as a teen to go to art school felt like a weirder coming out in my family because it wasn’t something practical as a profession. You weren’t going to make any money that way. When you come from working-class backgrounds, that’s of course what your parents are most worried about. I think I’ve always been weird and strange to my family because I’m an artist, and that’s probably the first marker of difference.

I think the queerness part is, “Well, OK, might as well have expected it. He’s an artist.” I don’t know. It’s interesting. In short, I would say it has its challenges. It’s certainly hard. There are different levels of difficulty and struggle and self-acceptance that I’ve had across my life, but I’m really tied to my family and their ways. I think it’s special. I didn’t realize it as a teenager, but it was really special to come up in a craft tradition. Many people don’t. Another way to answer your question, why do I quilt, why do I do textiles? It’s actually the first thing that comes to mind when I think of an idea. This is the first thing that was put in my hands as a material I could be creative with.

Pier Carlo: It’s almost like a sense memory.

Aaron: It is. It’s a haptic experience. An embodied experience is how some people might want to academicize that. It is my go-to, it’s my autopilot. When I am quilting, I am in my natural space of creativity.

Pier Carlo: You used the word acceptance in relation to your family, and I want to pull the lens out wider and talk about acceptance within the art world. I know that in recent years I’ve seen so much more writing and exhibits of fabulous contemporary fiber artists like you. But I’m curious if you have ideas about what could still be improved or change in the art ecosystem to ensure that upcoming fiber and textile artists receive the same kind of opportunities and recognition as other top artists in the fine arts?

Aaron: Well, I get this question a lot these days, as you may or may not imagine, so it’s not an unfamiliar one to me. A semantic thing that I want to do with you and for this interview is to just remind anyone listening that fiber and textile arts are fine arts and they always have been. [He chuckles.] When you go to any major art museum in the world and you look at certain ancient cultures, you’re going to see that cultures prized making and sharing their iconography, sharing their religious views, their important people, their gods, their cosmologies, and they found just as much relevance in sharing those ideas and commemorating them through textiles as they did things like stone carving, woodworking, metalwork, jewelry, sculpture, etc.

Pier Carlo: The problem is, as you know, fiber and textile don’t survive through the ages as easily as stone and ceramic, so we actually have no idea the extent to which fiber art exists.

Aaron: Oh, we have some ideas. We have a lot of ideas. We actually know a lot thanks to feminist scholarship beginning in the 1970s. Just a short example: Elizabeth Wayland Barber is the most prominent person who comes to mind for this, a feminist-oriented archaeologist and ethnographer, who has analyzed the object-oriented aftermath of when the British were discovering and raiding Egypt’s tombs and bringing all of those artifacts out. So many of these things within the sarcophagi and other things that were mummified were wrapped in cloth that would have been, of course, hand-woven, hand-spun, hand-harvested linen. All of these textiles did survive, but the archeologists at the time just didn’t keep it. They threw it all away because it was considered waste, because textiles were not seen as valuable, and perhaps that’s because they had been closely associated with women’s work during the Victorian era.

The movement was led by a number of artists — who did tend to be women — beginning in the 1930s roughly to the 1950s who were trained in textile design and who started making sculpture, wall-bound objects, pictorial art, things that were not design objects. It led them to build the foundations of what has had many different names: textile arts, fiber arts, the fabric art movement, the fiber movement, the fiber arts movement. And you have a number of prominent people, all of whom are women, and they really do struggle to get a lot of traction.

There was a sort of a “hotness” around fiber in the '60s, where it meets the hippie movement, and everyone is suddenly interested in macrame and all these other sorts of things. Crochet, quilting and needle arts have a renaissance in 1976 of the American Bicentennial, and everyone gets into heritage crafts. That adds another element to the fiber arts movement of the '70s. It sees itself as its own field, but it has always — not on its own terms but by the terms set by others — either been welcomed into or shunted away from fine arts. You have even famous feminist artists like Louise Bourgeois, who very famously wrote a really critical review of fiber artists, stating that using textiles and using things connected to the domestic sphere is fundamentally not art. There’s quite a bit of course correction to be done with generally how we talk about these histories.

Pier Carlo: Has that course correction happened? Is it happening?

Aaron: I think it’s happening, and it comes and goes. If you’re in this field, especially if you teach in this field and you’re with other fiber textile colleagues, it’s like yet another eye roll when someone writes a Hyperallergic article about discovering Lenore Tawney, for instance. Or right now at the Fondation Cartier in Paris there’s a woman who’s been a part of this movement, again for, we’re looking onwards now of 60 years. Olga de Amaral from Colombia is having this huge retrospective. There have been a number of retrospectives of her work over the years. They’ve just not been in this blue-chip global art world. The commercial art world has been late to catch on to fiber art.

Pier Carlo: Your bio states that you’re committed to transforming and diversifying the next generation of fiber textile artists. Could you describe what you mean by that? Have you gone about doing that?

Aaron: I put that statement in my bio because it is an important thing for me. The field, at least in academia as it was taught when I was growing up, was really rigid and really different. I remember being told that I shouldn’t really put my queerness in my work because that’s not what art is about or that’s not what craft is about. I should make the kind of work that invites anyone to consider it, and doesn’t make people who aren’t queer feel like they can’t understand it. Anyways, I found those very frustrating critiques of the work when I was a younger person.

Then at the point of entering the field and being a teacher and being on the other side of that table, it was like, well, I want to always be a voice for people who do want to share their story, share their identity and their work and be a non-judgmental and very open and accessible person, a professor who will be supportive of that kind of identity-based work.

I also am just really committed to this field, [laughing] if you can’t tell from my diatribe and semantic correction for you about who is in it and what genders are at play. There is not a culture on the planet that doesn’t have a textile tradition. There are many cultures on the planet that don’t have proper painting traditions or drawing traditions or sculpture traditions, but every culture on the planet has a textile tradition. This makes us, just naturally speaking, globally speaking, one of the most diverse fields.

As a field it’s huge. Sculptors can work with anything, but ceramicists are always working with clay. Metal workers are always working with metal. But in fiber we have basketry, we have net-making, we have knitting, quilt-making. We have surface design, the whole world of dye work and embellishment. You have weaving. I mean, it’s a giant field with a lot of different sub-disciplines. It’s naturally diverse, just material- and technical- and methodology-wise. But we — those of us who make up the field now, and who are invested in these different traditions and their futures — are also a more diverse crew than my time as a student.

December 02, 2024