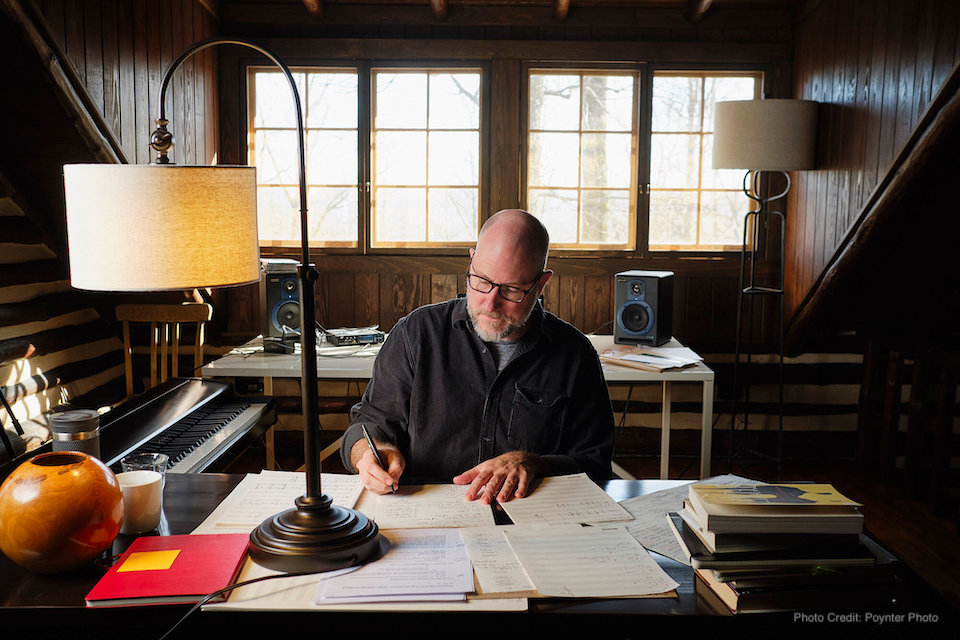

Brian Harnetty

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For sound artist and ethnographer Brian Harnetty, listening is perhaps even more important than composing. He is passionate about capturing the essence of a place through his creations, and his work therefore involves venturing into towns and landscapes armed with his microphone and recording everything from ambient sounds to oral histories. It also involves in-depth research in archives and libraries to discover a community’s often forgotten history, images and archival recordings.

The geographic area to which he is most devoted is Appalachian Ohio. His parents and their forebears hail from those mountains, and though he currently lives a 90-minute drive away in Columbus, OH, over the years he has spent enough time in the area not only to gain a deep understanding of its landscape and people but also to earn the community’s trust, an essential component of his work.

He wishes his compositions — sound collages might be a better description — to have a social impact. Not only do those who listen to his creations gain a rich appreciation for a region that for decades has been marked and scarred by extractive industries, but the community members who contribute their memories hear the richness of their culture and history echoed back to them.

Brian, who is currently a Faculty Fellow at Ohio State University’s Global Arts and Humanities Discovery Theme, has released nine albums. The influential music magazine MOJO gave two of his most recent albums, “Shawnee, Ohio” and “Words and Silences,” five stars out of five, and “Wire” magazine placed “Words and Silences” at position number five on its top 10 list of 2022’s modern-composition albums.

In this interview with Pier Carlo Talenti, Brian explains how he arrived at his sonic ethnography practice and what strategies he uses to make his work with the utmost integrity.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- What came first, your interest in people and places or in music?

- Can you give me an example of ethical questions that you had to work through?

- What is involved in building trust with people whose archives and interviews you might use?

- How over the years have you cultivated this practice of listening?

- What’s been the reaction when community members have listened to your pieces?

- What have you learned from the process of “Forest Listening Rooms”?

- What would make it easier for artists such as yourself to be rooted in a community and stay in constant communication and collaboration with that community?

- How does your work fit into the contemporary composition scene? Is that at all important to you in terms of recognition?

- If somebody were to call you and say, “Hey, I want to commission you to create a piece about my community,” would that be interesting to you?

- What current or upcoming projects are you particularly excited about?

- In terms of looking at your career as a socially engaged artist, what is the change

you most want to influence?

Pier Carlo Talenti: What came first, your interest in people and places or in music?

Brian: My earliest childhood memories are around place and people, but I don’t think I really

processed them until later. So, I would say composition first.

I grew up studying classical music and composition, and the ethnographic writing and

techniques came much later as an adult in my thirties. I had all of these ethical

questions around place, around using sound archives and sampling, and the anthropological

methods gave me a toolkit to be able to work through some of those questions and problems.

Pier Carlo: Can you give me an example of ethical questions that you had to work through?

Brian: Sure. When I first started composing, I was really interested in musical borrowing, and my teacher in England, Michael Finnissy, was very well-known for doing this. It has a long history going back to Charles Ives and beyond and before that. I was very much interested in using borrowed musics and sampling and then creating collages out of them. At first, it felt very freeing and that everything seemed available to me, but the ethical questions that arose out of that were, “Should I be using anything that I want to? [He chuckles.] And should the people attached to those recordings be considered as well as part of a project?”

That began a long process for me to create more established relationships with both archivists and historians around particular collections and also with the families and the people that were directly connected— whether by culture of familial ties — to the recordings that I used. It completely changed the way that I thought about sampling and using archival materials, and it also completely changed what I used and how I used it.

Pier Carlo: How so?

Brian: For example, one of the first archival projects that I did that was more formal was in Berea, KY, at the Appalachian Sound Archives there. I was invited to go there, and I was doing a lot of research in the archives, listening to many recordings, in particular the recordings of a woman named Addie Graham. She was in her nineties in the 1970s when these recordings were made. I just fell in love with her voice and her personality.

It was just a few days later that I went to a party down in Whitesburg, KY, and I happened to meet her great-granddaughter. It was at that moment — it was like a revelation or a little epiphany or something like that — that I was like, “Oh, of course the recordings are connected to people. They’re not just inanimate objects. They actually have their own agency, and they can be activated. And there are people that are deeply affected by these recordings because it reminds them of their family members or of a place or time.”

That was a way for me to think, “How can I involve community members in my projects? How could I think of them as my main audience? How can I return what I’ve made back and share it with them and get their feedback?” Also getting their permission is a really big piece of it too. For example, when I worked with the Sun Ra El Saturn collection in Chicago, which was all based on the experimental-jazz composer and band leader Sun Ra, I entered a contract with the archive and also with Sun Ra’s nephew, who was the holder of the trust and copyright.

Pier Carlo: And what did that contractually involve? Does the archive or the heir have any ownership of your work?

Brian: The way that that contract worked was I got permission to use the recordings — they invited me to use them — and then I had to share what I made with them, and then it went through an approval process. They could have said no at any point, and I would’ve just needed to accept that.

Pier Carlo: That must have been terrifying. Describe that.

Brian: [He laughs.] Yes. Well, it was a long process of establishing a relationship too. I think by the time I got to that point, I knew that there was a certain kind of rapport with the people in Chicago who held the archival recordings and that they had a certain amount of trust in me as well. It wasn’t out of the blue or anything, and it wasn’t just a cold email asking to use something. It was part of a longer, much more involved process.

Pier Carlo: Describe that. What is involved in building trust with people whose archives and interviews you might use?

Brian: Sure. Well, I’ll use my work in Appalachian, Ohio as an example, because that’s been the longest relationship. Also, this brings it back to the ethnographic writing and thinking.

In 2010, I first started to visit Appalachian Ohio, which is where both of my parents’ families are from. But I’m not from there, so I was a bit of an outsider but with an introduction card from my family members.

Pier Carlo: How far is Columbus from there?

Brian: It is not far. It’s about an hour and a half from there.

Pier Carlo: But culturally, a different world, I’m guessing.

Brian: Very different world, much more rural. It’s in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. Ironically, over one third of Ohio’s counties are part of Appalachia, but oftentimes it’s not really thought of as or it’s looked over as being part of Appalachia. And it also has a long labor history around extraction and mining, which ties it in with that region as well and perhaps an earlier one starting in the 19th century.

I had started to do some ethnographic research in the region, but it quickly became a story of place but also of the people that were there and then my own family history of that place. Specifically, I focus on the sounds of a place, so I call it sonic ethnography. There’s a long history of that too. It’s really using sound as a tool to understand a place and its people and how they understand themselves and derive meaning from that place and the culture.

My time there started in 2010. What started off as a scholarly project where I’m just deeply paying attention to people and places, I’m hanging out, going to public meetings, to festivals, to parties, and then I’m making friends —

Pier Carlo: You have a microphone the whole time?

Brian: [He laughs] Not the whole time. Certainly not at first. It can be quite intimidating. I didn’t want to come across as being someone just coming down to take something and then splitting.

Pier Carlo: Extracting in a place that’s been destroyed by extraction.

Brian: [Laughing] Yeah, cultural extraction is a real thing.

And then I spent a lot of time building those relationships up, getting permission to do interviews and talking, and then I just started asking whether people had made recordings themselves of their family members or oral histories of the region. That led to essentially an informal archive of tape recordings of about 40 cassettes that people shared with me, and then I digitized that. Then that became the basis of numerous creative projects in the region that explored that history of extraction, the silencing and essentially the extermination of the Indigenous population there, and also environmental destruction and recovery and economic booms and busts and so on and so forth.

There was a lot of very rich, difficult, but also often very beautiful material that was there. Using ethnographic writing and paying attention and participatory practices allowed me to not be a part of the community but to have a meaningful and respectful relationship with the community members.

Pier Carlo: What did you learn along the way that you hadn’t really known, even though you had parents who grew up there?

Brian: The long-term destruction of the land, ever since, I guess, mostly European, mostly white settlement 200 years ago. There’s been extraction in one form or another, be it first the timber, iron ore, clay, obviously gas and oil. The latest iteration is hydraulic fracturing or fracking.

Then just the really strong pride of the people in the land and the long history of labor struggles. It was the very place in the 1880s where the United Mine Workers was formed, and so it has a very strong, very interesting past that is often overlooked in that way.

Then the other really surprising thing is its recovery and resilience. By the 1920s, the entire area was completely clearcut. There weren’t any old-growth trees left, and I can’t think of a more sort of desolate understanding of extraction than that. But at the same time, as part of the New Deal, Franklin Delano Roosevelt decided to declare the area a national forest, even though there weren’t any trees there, which is a really bizarre social experiment if you really think about it. [He laughs.]

As part of that initiative, they reseeded the entire area, and now it’s a forest where the trees are almost 90 years old. It’s not old growth, but it very well can be in the coming decades and century. So that to me was a spark of hope in the region that I found very heartening.

Pier Carlo: Are the communities of people regenerating in some way?

Brian: Yes and no. I think that it has had many decades of economic decline alongside that environmental degradation, but there are these pockets of communities that have been rallying around both the environmental benefits that have been happening — acid-mine drainage-mitigation efforts have really brought back a lot of the natural flora and fauna that used to be there — and the economic development around what I like: people-centered, community-centered economies. That means not relying on large companies to come in and offer a few temporary jobs at the expense of extraction, with most of the money leaving the region, but smaller communities focusing on, for example, retelling the stories of the place or focusing on environmental recreation, the kind of stuff that really brings more people to the region and allows people to stay who might have moved away otherwise.

"Perhaps most importantly is to forge long-term relationships with key community members and then keep coming back. If you go in with all of your ideas rigidly thought through, that won’t allow you to accept another person or reveal your own vulnerability almost. If you’re truly listening, you are doing that. You are in a vulnerable position. You’re both speaking and taking in what other people are saying, and you’re not formulating your answers too fast."

Pier Carlo: How over the years have you cultivated this practice of listening? What’s been involved?

Brian: Well, it’s on a few different levels. The most basic level, in a way, is to make field recordings, to just to go out into places and to listen through a pair of headphones and see what that’s like. That’s one way. Another way is focusing on research, trying to listen to photographs or archival recordings and so forth. That’s been an important part.

But perhaps most importantly is to forge long-term relationships with key community members and then keep coming back. If you go in with all of your ideas rigidly thought through, that won’t allow you to accept another person or reveal your own vulnerability almost. If you’re truly listening, you are doing that. You are in a vulnerable position. You’re both speaking and taking in what other people are saying, and you’re not formulating your answers too fast. There’s a whole host of tools that you can use, but the coming back piece and the time piece in connection to the community members might be the most important.

It feels like unfortunately most artists are unable to do that. They have to move on. They can only stay in a place for a few weeks or a few months, and then they have to move on to another project. I feel very fortunate that I’ve been able to spin out with the same relationships a series of projects in the region that have allowed me to keep coming back.

Now, this also means that I’ve become very much connected to a lot of the non-profits in the region, and in fact, I’ve done a lot of work with them and also sit on a board of a non-profit and have become — not a full member because I don’t live there and I don’t think I’ve maybe spent enough time —maybe a friend of the community in Shawnee and the surrounding towns.

Pier Carlo: Speaking of listening, what’s been the reaction when community members have listened to your pieces?

Brian: Perhaps the most amazing experience was when we created this project called “Shawnee, Ohio,” and we premiered it in Columbus at the Wexner Center for the Arts, which is a much more formal arts venue. It was wonderful to see so many people from Appalachian Ohio come to a venue like that, and the Q&A session afterwards was really wonderful.

But then the next day we took it down to Shawnee and performed it in a century-old theater that’s there. In fact, this was a theater where my grandfather used to play music in the 1920s.

Pier Carlo: Oh, he was a musician as well?

Brian: I mean, he was the captain of the basketball team, so they’d all play basketball

on the flat floor of the theater [he laughs], but then he was also in the orchestra,

so then they’d put the chairs all back and have concerts there as well.

That theater was very special, obviously to me but also to the community, and I feel

like half the town showed up. We had a big potluck. Everyone’s sitting around eating

and drinking coffee or beer or whatever, and it just felt very celebratory. Then afterwards,

everyone talked about the images that they saw and the recordings that they heard,

how they might relate to them, whether they saw a relative of theirs in the photographs.

It was just an extraordinarily special moment that I was able to witness.

It spurred me onto many other projects where I wanted to work with listening directly in the community, for example a project called “Forest Listening Rooms,” which is a much more deeply socially engaged project where I am just taking community members into the Wayne National Forest just to listen. In silence, we listen to archival recordings, again, of people that lived there before. I take a backpack with me with a few Bluetooth battery-powered speakers.

I’m playing sometimes in the very spots where these people worked in old former mines, for example. There’s a small cave called Robinson’s Cave, which is the birthplace of the United Mine Workers, and we’re listening to people talk about those places. So there’s a haunting quality there, but it’s against the contemporary backdrop of a now-thriving forest that feels almost like it’s taking over in really wonderful ways. So you are able to hold both the cautionary tales of the past but also the pride in the land and people’s work there and also the hope that’s happening in the present moment for the region’s future.

Pier Carlo: And what have you learned from the process of “Forest Listening Rooms”?

Brian: [He laughs.] Well, at first, the surprising thing shouldn’t have been surprising at all: No one really wanted to follow me into the woods at first just to go listen. Right? It seems a little bit crazy.

Pier Carlo: Also, people are not accustomed to gathering in order to be silent with one another.

Brian: But there was a sort of ritual aspect to it. I mean, I think of the Quaker tradition, which does exactly that.

But yeah, it’s funny that no one wanted to come out at first, so I had to go undergo a process of rethinking what a “Forest Listening Room” meant. The first thing I did was I became an AmeriCorps volunteer for the year in Shawnee. That just got me on the streets and working in Shawnee every day for a year. And of course you’re going to meet people and bond with them during that time.

The second thing was that I didn’t try to have a huge gathering of people right away. I decided to meet local residents on their own terms. For example, someone might invite me to their house, and then we’d go out in their backyard and listen for a bit. Someone invited me to their childhood play area, which had been strip-mined and was destined to become strip-mined again, and so they were expressing their concerns over that.

I also went out with people that I call almost like unusual allies, people that might be on the opposite end of the political spectrum from me or think very differently culturally. So, for example, I went out hunting. [He laughs.] I wasn’t hunting, but I went out with hunters as they were hunting. I had my shotgun microphone, and they had their shotguns with them, and I just observed how respectful they were of these public lands.

Pier Carlo: Very few people love the forest as much as hunters.

Brian: That’s exactly right. Even though they might think differently, for example, about taxes or how the government should be used or guns, they were more than willing to support these public lands because they understood not only what they could get out of them but what the land’s value is for everybody. That was really encouraging.

Also there are ATV drivers, like pleasure drivers, in the forest. They have designated areas where they can ride around. To me, it’s too noisy, it’s too loud, but to them in those designated areas it was very a special experience. Also they were struggling and working hard and raising money to fight off new extraction in the region, to help protect not only the lands that they use but the other public lands around it. There’s this understanding where all kinds of people can get together and focus on the land itself and how to protect it.

"When I was living in the UK, I just figured that I would just stay there or be in Europe somewhere. In fact, many of my friends stayed on and moved to Berlin or Paris or whatever, and that sounded so wonderful to me. But I had a teacher who said, 'Wait a minute. I think you have something you need to address back home, and maybe you could just spend a little time there and figure it out.' And of course, I’ve been doing that for 20 years now.”

Pier Carlo: I feel like every small community should have a Brian Harnetty, but as you mentioned, that’s very difficult for artists to achieve, staying rooted in a smaller community. What would make it easier for artists such as yourself to be rooted in a community and stay in constant communication and collaboration with that community?

Brian: Well, I mean, as an artist, I recognize that there’s a lot of pressure for artists to get out there, to get their names known, to be in a large cultural center like New York or L.A. or Chicago or something like that, and to make their mark. It makes sense to me. But I also recognize that at some point it’s also an option to be able to stay, to stay in more rural places, to stay in places that you might have connections to with your family history and to make work there too. That is just as valid and interesting as anything else. That would be my biggest thing: Don’t be afraid to stay and see what might come of it. That’s certainly been my journey.

When I was living in the UK, I just figured that I would just stay there or be in Europe somewhere. In fact, many of my friends stayed on and moved to Berlin or Paris or whatever, and that sounded so wonderful to me. But I had a teacher who said, “Wait a minute. I think you have something you need to address back home, and maybe you could just spend a little time there and figure it out.” And of course, I’ve been doing that for 20 years now.” [He laughs.]

I think it’s really good to go away for a while. I think it’s also really good to not be afraid to invest your efforts into those local things too, because there’s so much meaning, and there are many rich stories to be explored. Artists have a really wonderful and unique way of understanding the world, and community members of these small communities do appreciate it, especially when it’s done with a certain amount of stewardship and mutual respect.

Pier Carlo: You mentioned having impact as an artist. How does your work fit into the contemporary composition scene? Is there a slot for an artist like you? Is that at all important to you in terms of recognition? I don’t know how it works.

Brian: [Laughing] Well, honestly, I’m not 100 percent sure how it works either. Yes, my training is in classical composition, but I’ve always had an interest in other disciplines, an interdisciplinary interest. In fact, the merging of music or sound with other things — with film and video or writing or anthropology, for example, any number of other disciplines — is just really what gets me the most excited. As an interdisciplinary artist, I think you often do fall between the cracks and nobody really knows what to do with you, but at the same time, there’s so many possibilities and openings if you’re just willing to pay attention to them.

I would say right now in retrospect it seems like a very nice, neat, tidy story about my career over the past 20 years. It all has a logic to it. But in fact, when I’ve been going through it, it all seems unknown and very, very uncertain. Each time I followed my instinct. A good friend of mine from Kentucky suggested going to Berea, for example. Once in Berea, I forged some really nice friendships there, and then that made me interested in Appalshop and Whitesburg. And then oddly enough I found myself in Chicago, and then I found myself in Appalachian Ohio, and now I’m back in Kentucky again. It just seems like each time this one thing leads to another and if I get out of my own way [he chuckles], I can think like, “OK, what might this present? What opportunities might this hold?”

Pier Carlo: Getting out of your own way. What’s the first reaction?

Brian: I often think, like many people do, should I be doing something to try to be noticed or get my name out there somewhere? But in fact, the second instinct is, “Actually no. This thing, nobody might pay attention to it, but that’s OK because it is really interesting to follow.” Just allowing that sense of curiosity and openness to guide you instead of thinking about one’s career all the time or something along those lines.

Pier Carlo: If somebody were to call you and say, “Hey, I want to commission you to create a piece about my community,” would that be interesting to you? And if so, how would you proceed?

Brian: I’ve thought about this a lot lately because after 12 years of working closely with the communities in Appalachian Ohio, I see that as almost a lifelong project, but I also am curious about other things in places too.

One of the solutions that I’ve come up with is that for the “Forest Listening Rooms” project in particular I’ve been doing some writing around it and thinking about, “Well, what are the listening strategies that I’ve used?” And I write those down. And then also, “What are the community strategies that I’ve used, specifically around the idea of socially engaged art?” And then thinking, “How could I create some writing around this or some prompts so that anyone could do this, no matter where they are?” It doesn’t necessarily have to be me in each one of these places, and I might not even be doing it justice. There might be a local person that has more knowledge and more connections than I ever would, and they might lend insight to a project that I wouldn’t be able to offer.

That’s one way of thinking it through, offering the techniques that I’ve used, especially around listening and recording and thinking through ways for others to do that no matter where they are.

Pier Carlo: What current or upcoming projects are you particularly excited about?

Brian: The current project that I’m working on right now is called “Words and Silences.” It’s a sonic portrait of the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, who died in 1968. We just had the premiere last week actually at the Wexner Center for Arts in Columbus. It was a magnificent experience. I’m still sort of like high on a cloud about it all.

Pier Carlo: Describe the experience. Why was it so magical?

Brian: Well, I did most of the composing just before the pandemic, and the musicians all sent me their parts through the internet, so I wasn’t able to see them when I made the album. So when we all got together — it’s myself on piano and a quartet of trumpet, trombone, alto sax, flute and bass clarinet — when we all got together to practice and rehearse, it was just so wonderful to hear everything in person, of course. The musicians were just really top-notch musicians. They made me a better musician, and it just made the performance really special.

Then the next day, because I’m so interested in the idea of place, I took the whole band down with me to Thomas Merton’s hermitage, which is in Kentucky, about 40 minutes outside of Louisville. We performed the entire work in his hermitage, in the very place where the recordings that I used of him were made, and so there’s a real sense of place of the architecture of the building and the sonic acoustics of it informing our own performance. Also the fields and the woods around. That was just a very special moment.

Pier Carlo: That was a crucial part of the project.

Brian: Yes.

Pier Carlo: Did you record that session?

Brian: We did.

Pier Carlo: Of course.

Brian: We definitely documented it with both video and audio. I’m not sure what will become of that, but it just felt like such an urgent need to do it that we decided to make it and then [laughing] figure out later how it might live in the world.

Pier Carlo: And in terms of looking at your career as a socially engaged artist, what is the change you most want to influence?

Brian: It’s almost impossible to measure. Certainly with a project like “Forest Listening Rooms,” for example, it might take decades to even see impact that I am not even part of, just impact in the region. First and foremost, I feel if I could be a witness to a lot of the community members’ efforts to revitalize and recover the land and the economy there, I think that that’s something. It gives amplification to the voices that are already there without me having to add my own ego or commentary on it. That’s something that I’ve been very interested in.

For example, a woman that I did a “Forest Listening Rooms” session with, her name was Jolene Dixon. She was part of a community that was fighting against a new strip mine taking place in the forest. I walked with her, and we made a beautiful little film with her, and her voice became part of the project. I didn’t have any impact on this, but I was able to witness it, that eventually through their efforts, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources backed away from that new coal-mining effort. So I felt very proud to just be there, but I wouldn’t lay claim to it as the project having done that. The project was just present, and I think that for impact, that’s about as good as it can get in a really nice way.

Pier Carlo: It’s very humble, this idea that your listening is more important than your work, than your noise-making, as it were.

Brian: Yeah. I forget the actual quote. There was a composer named Alvin Lucier who said something like, “Careful listening is more important than virtuosic playing.” That’s my paraphrase, but to me that makes total sense. Sometimes just getting out of the way and listening can be just as meaningful a sonic listening experience as trying to compose something very carefully. They both have their place, but I realize that sometimes the more I get out of the way, the more exciting it becomes. There’s really something there.

February 07, 2023