Art 25

Listen to the interview on Apple, Spotify, or your listening platform of choice. Captioned interviews are available on YouTube.

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What happens when best friends in different disciplines decide to formalize their creative relationship and then invite a third artist into their artmaking experiment? A vibrant, equitable and joyful collective by the name of Art 25: Art in the 25th Century is born.

Art 25’s core artists are poet Lehua M. Taitano, visual artist Lisa Jarrett and multi-disciplinary artist Jocelyn Kapumealani Ng. Separately, Lehua, who is CHamoru; Lisa, who is Black; and Jocelyn, who has Hawaiian, Chinese, Japanese and Portuguese roots, had been exploring similar themes of identity and diaspora in their artistic practice. Fusing their talents and perspectives, however, allowed them access to an even deeper well of experience and imagination from which to draw inspiration.

Since Art 25’s founding, the collective’s work has been seen at several institutions, including the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center and the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco, and in February of 2025 it will be exhibited at the Pacific Island Ethnic Art Museum in Long Beach, CA.

In this interview, Lehua, Lisa and Jocelyn describe how they joined their creative forces and explain the core anti-capitalistic values of Art 25 that not only place it firmly outside the artistic mainstream but continue to bring them joy.

Pier Carlo Talenti: I would love to know how you three know each other and how the idea for this collaboration came up.

Lehua M. Taitano: Lisa and I have known each other for years and years and are friends but family. We had the idea to start collaborating together around 2017 for a project by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center. I had the opportunity to showcase some art, and I asked them if I could collaborate with a friend. Fortunately they were open to it.

Lisa and I also attended graduate school together but in different disciplines. We both went to the University of Montana and got MFAs. I got mine in creative writing, and Lisa’s is in visual art. We had worked alongside each other but never truly collaborated on a specific art installation or project before this.

We collaborated on a project for that Smithsonian exhibit, and it was in Honolulu where we actually met Jocelyn but just in a kind of passing way. We didn’t actually connect with Jocelyn until much later, but she was also there for this exhibit called “Ae Kai.” It’s one of the Smithsonian APAC’s Culture Labs. There were over 50 artists there, and Jocelyn was one of those artists. Lisa and I, from that point on, basically said, “This is it. This is kind of the link that’s been missing.”

Pier Carlo: Can you talk about what that link was?

Lehua: I think in our creative relationship, it was just the idea to collaborate together. We had been working, writing poetry, writing short fiction and essays; Lisa is creating all kinds of multidisciplinary visual art; and the missing link was, what if we combined forces and put those creative powers together? That’s really when the idea for Art 25 first began.

Lisa Jarrett: Lehua, can I add one thing to that?

Lehua: Please.

Lisa: To respond to this idea of what was missing, thematically in each of our respective practices prior to Art 25, we were addressing similar sorts of topics, trying to address and understand diaspora, identity, Indigeneity, Blackness, all of these things but really within our separate pillars. And so the conversations we were having with each other were sort of consultations like, “I’m trying to work on this. Let me run this by you. What do you think?” Or just wherever those conversations would go.

I think I want to add to Lehua’s story that this idea of directly building something together seems so obvious, but it was kind of a radical realization for us at the time.

Pier Carlo: It’s kind of formalizing what had been informal consultations, it sounds like.

Lisa: I would say so and then maybe also working on one singular ... singular is too limited of a word. Lehua would be working on a writing piece, and I would be working on, let’s say, an installation, and that would be a Lisa Jarrett installation, and there would be a Lehua Taitano poem. But we had not yet worked on a Lehua-and-Lisa singular work of art. I think what I’m trying to communicate is that we were now collaborating on a singular thing together as opposed to referencing one another’s work and practices in our respective lanes, if you will.

Pier Carlo: And Jocelyn, how did you enter the fold?

Jocelyn Kapumealani Ng: Going back to what Lisa and Lehua previously mentioned, I met them in passing at the Culture Lab. It was a real brief introduction to one another. It wasn’t until about a year later that Lehua messaged me asking to hop on a call, inviting me to collaborate. I think we were on the phone for maybe an hour, and I was very gung-ho about it. I was like, “Let’s do it. That sounds great.” I love collaboration. I think my whole practice has always been in collaboration with others.

From the get-go, they just came to Hawaii, and I think the rest is history. Everything just clicked. The vibe was right, and it was so easy. I can’t emphasize enough. Everything was just so easy.

Pier Carlo: How so?

Jocelyn: From conversation to thinking about ideas. I was very transparent with them of where I was at with my own practice, where I was in my personal life. My grandmother had just passed away. I think one of the first conversations I had with them was, “Hey, I understand you guys are here, but this is where I’m at personally, and I haven’t really been making art, but this is what I’ve been feeling. I don’t know if this is what’s calling me right now, but if we can incorporate this somehow, I think that’s where I’m being moved to.” And Lisa and Lehua were so open to everything.

Pier Carlo: Did you incorporate it?

Jocelyn: Yeah. When we collaborated for “Future Ancestors,” the transformation aspects of what I did on my own body with the scarring was an echo of the scarring on my grandmother’s body when she was fighting cancer. Incorporating those aspects was really important and powerful to me.

Pier Carlo: Could you describe “Future Ancestors” and talk about how as a threesome you were able to achieve something that you could not have achieved on your own?

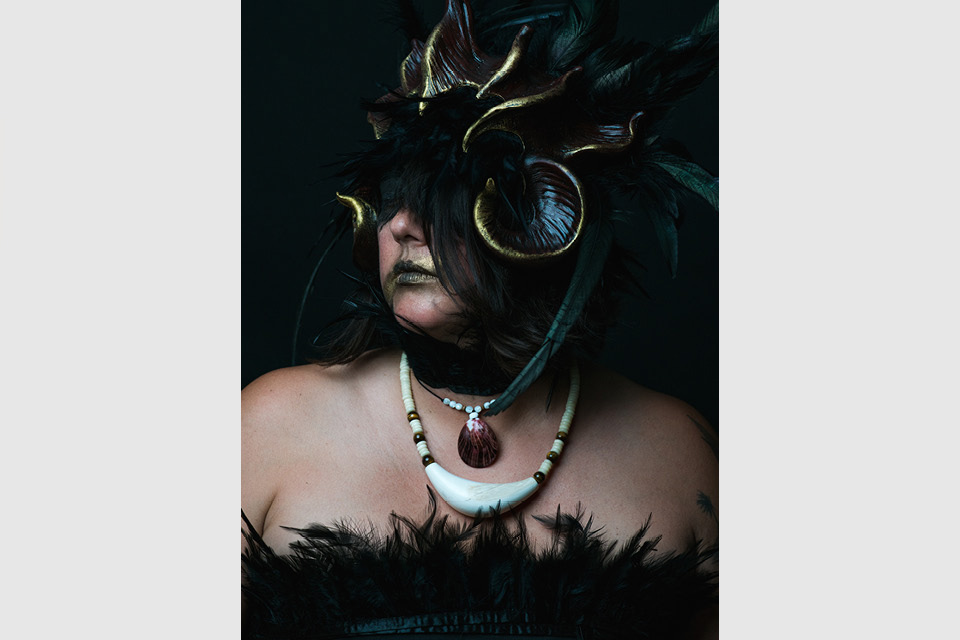

Lisa: Yes. Let me back up just a second. This vision that Lehua and I had of collaborating with different artists was inherently connected to being interested in those artists’ practices. Jocelyn’s practice prior to us working with her had always included sort of physical transformations within the body. She creates these just absolutely stunning beings with a being. I don’t know how else to say it. It’s just the images were captivating.

We knew that that was an aspect of what we wanted to include within this idea of a future ancestor. How could we, in the present day, occupy the role of an ancestor for her? And what would it mean to try to embody that together? What would we want to try to communicate and preserve? And how? That was really the impetus for why our bodies became such a big part of it, because Jocelyn’s practice always also includes a lot of performance and a lot of spoken word. We were trying to work within those genres alongside my and Lehua’s respective approaches to contemporary practice.

What ended up happening was that Jocelyn was able to invite another friend in, Bryan — and I’ll let Jocelyn speak about Bryan in a little bit — who worked as the photographer on the project to try to capture what it meant or what it looked like for the three of us to interact in these transformed bodies.

The set of photographs that are the outcome or what we display or exhibit as “Future Ancestors” are really just artifacts of time spent together in this half-imaginary, half-real collaboration of existing as our future ancestors together. The storytelling that happened and what it meant to just be really, for lack of a better word, completely bare with one another, those were necessary pre-existing conditions to making this actually work. Any barriers that I would’ve had — I think this may be true for Lehua and Jocelyn as well — just had to fall away if we were going to be able to be our most true selves stepping into the work.

And then to answer the second part of the question, my practice has a lot of different tendrils. I work independently a lot, but I also work collaboratively a lot. I think that this project more than anything else is really not about what we made or how we made it so much as it was more this idea that we could build whatever we want if we just decide to do it and do it. I mean, it seems so simple, but the art world is the art world, and it does not leave you with that sensation. That was the real impact for me, and that resonates with me still today.

From “Future Ancestors,” Art 25, 2020; Photography by Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada

Pier Carlo: Lehua and Jocelyn, do you want to chime in on “Future Ancestors”?

Jocelyn: Going off of inviting my friend Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada to the project, I typically am a photographer, but I knew, with what was calling to us for this project, it needed another person with eyes that perhaps I could not capture. Bryan has always been one of my favorite collaborators, and I knew he was going to approach this project with such care. Inviting him in as a photographer was the right choice.

He is a professor at the University of Hawaii at the poli sci program. He is a Hawaiian-language translator and teaches writing and literature, but he is an amazing photographer. I can’t speak enough about how incredible his work is. I think he added an aspect to the project that brought all our ideas and the whole process of what we were transforming alive in a way that I personally didn’t think was going to come out the way it did. And if you’ve seen the prints … . To this day, I love them so much.

Pier Carlo: They’re beautiful. If you provide them to me, I’ll include them in our show notes so people can see them.

Jocelyn: Wonderful.

Lehua: Yes. We’ll definitely show you.

Pier Carlo: Future ancestors is such a wonderful and strange term. How did you all three agree on this title?

Lisa: [Laughing] Lehua?

Lehua: I will speak a little bit to this. I think this is kind of dovetailing on the question that you just asked: What can you achieve in collaboration that you can’t achieve alone? Part of that is discovering within yourself in relationship to other creatives in that moment when you are coming up with the ideas, the excitement of creation. It’s the what ifs. “What if we did this? What if we did this?”

I think that each of us is a mirror, or a prism maybe is a better term, for the other two people. What it allows us to do in conversation when we’re thinking about what we’re making is to reflect ideas onto each other but then to have those ideas processed a little bit through each brain, each set of lived experiences. When it’s happening, it’s electric. It is 100%. It’s that artist’s high that I get working in collaboration where you’re watching something unfold and you’re not just teasing out the solutions in your own head. You’re talking about it with other people who really understand you.

We have our own strengths, and I would like to think that one of mine is coming up with titles for things. [Everyone laughs.] I really like naming things. I like the process of naming. At some point, we were like, “What do we want this to be?” We’re each going to transform into this idea of, if our descendants were to look back at a photo album of us, what would they see? And they’re going to be those photos that are taken in each family. You’ve seen pictures of your aunties, your uncles, your grandparents, and they’re all posed, mostly. You can have a sense of what’s going on maybe for that person in that day, but how much does that portrait say who they are, how they envision themselves to be? That was the idea for creating ourselves into these larger-than-life portraits: What would we pass on if we could say, “Hey, this is me”?

One thing that became really important was thinking, “What do we want to say to our descendants about queer familial intimacy?” That’s where the portraits came from, this idea of capturing how we see ourselves and how we see ourselves because of each other, because of that collaborative relationship. The idea, the name “Future Ancestors” is, how do we encompass this idea of queerness, of familial intimacy that’s not romantic intimacy? And how do we capture it and make that available for those who come after us?

Pier Carlo: Speaking of names, I don’t want to overlook the name Art 25. How did you settle on the name?

Lehua: Lisa, feel free to jump in. Lisa and I in grad school used to watch the PBS show “Art21: Art in the Twenty-First Century.” We were like, “This is it. This is an example of what art is in the 21st century, and this is what the show is saying. These are contemporary minds and geniuses in the art world.” A lot of the shows are really wonderful, and the resource that it provided for us to have that lens to look through was wonderful.

But what was not reflected back at me was anyone who looked like me or identified as I do. I simply did not see CHamorus making art on “Art21.” I didn’t see Pacific Islanders making art in “Art21.” And I thought, “Well, if we’re not represented in the 21st century, how would it be in the 25th century? Can I envision CHamorus in the future making art? What is the limit of what I can imagine?”

“Art 25: Art in the 25th Century” is a little bit of a cheeky spoof on that, but I really do think it has the depth of meaning to actually be able to look forward and see what you’re doing now that enables other Indigenous, Pacific Islander, Black artists making and creating several generations into the future.

Lisa: There are two things I’d love to add to that. When we used to watch “Art21,” for me there was representation. There was a fair amount of representation of Black identities within contemporary practice in “Art21,” but there was also this missing piece of ... . This is people at the top of their game. This whole middle space, which is the working life of an artist to get there, was just glaringly absent. I don’t say this as to offer a critique of “Art21” per se, but I’m just noting the absences. That was sort of this gaping thing when we would look back on it. How do you ... ? You’re looking at these people in these huge studios with all these assistants and all these things.

Pier Carlo: Because you’re looking for the how-to manual. Sure.

Lisa: You’re in grad school. You can’t afford dinner. There’s this gap between. And so trying to understand the void within this very small microcosm, but then as you would expand that out. The capturing of the void, the thing that’s not there, became important to us.

And then I guess anecdotally, I could share … . Lehua, if you want this excised from the record, please state, [laughing] but one of the conversations that we would have would be, “What do you think it’s going to be like when we are a they? When we’re a them?” Meaning —

Lehua: [Laughing] Oh, when I become Mel Chin?

Lisa: Right. When people refer to you as, “Well, they say … ” It’s sort of, how do you get in the canon? That’s really the hilarious way of being, how do you —

Lehua: And will I be a magnanimous ruler once I arrive? More importantly.

Lisa: Lehua is a Leo, and we should just say this for the record. Magnanimous ruler, of course. I mean, it’s this confluence of all these ideas — I choose the word confluence really intentionally — that led us to these moments of, “What is it that we’re missing? Oh, yeah, we just do it ourselves. That’s how it gets done.” You just make it happen. You give yourself permission —

Lehua: You want to be an artist, you just give yourself permission to make art and make it how you want to make it with who you want to make it.

Pier Carlo: It sounds also like, working in collaboration as you do now, you do feel like you have more permission than you might’ve given yourself before.

Lisa: Yeah, because it’s not relying on an institution. The status quo, the pre-existing condition, is that an institution is what validates your practice, right? That is the thing we’re taking out of this.

Pier Carlo: But does Art 25 still not work with institutions?

Lisa: We’ll work with institutions, but we don’t need institutions to work.

Pier Carlo: Say more about that.

Lehua: I’ll speak to this in one way. Art 25 is self-funded. We don’t sell our work, so it cannot be collected. The tangible material work that we make cannot overtly be collected by whoever has the money to buy it. We give our work to people in the community who want to steward it. We don’t do commissioned work. We basically just give ourselves the freedom to conceptualize and make whatever we want for us.

We are the target audience and all of our concerns that come with who we are as individuals. For me, it’s a CHamoru community; it’s an indigenous community. For Lisa, it’s a Black community. Those things also overlap, but we are making things and putting them into the world because we want to, and we do it how we want to, and it’s not aligned with an institution that is funding us and therefore possibly dictating the size and scope or duration of what we do.

Pier Carlo: How did you decide on this particular framework?

Lehua: I’ll say, and then I’ll maybe hand it to Lisa and Jocelyn next. Yes, I think that we come to this with similar but also individual perspectives on how we arrived at what we want it to be, and it sounds really simple, perhaps because it is. For me, the only rule to Art 25 is for it to be enjoyable. Period. That’s it. That is the goal. If it stops being enjoyable, then we’re not doing something right. And the least enjoyable thing I can think of is getting intertwined with capitalism even more and being entrenched and enslaved to late-stage capitalism for the one thing that brings me the most joy, which is connecting with people I love and being completely open and vulnerable to create and shape and make what comes from the depths of my being, which has nothing to do with money whatsoever.

For me, the only rule to Art 25 is for it to be enjoyable. Period. That’s it. That is the goal. If it stops being enjoyable, then we’re not doing something right.

Pier Carlo: You said something beautiful about, rather than selling your work, choosing to give it to community members to steward. Could you talk about that?

Lehua: I will say that the idea of stewarding work is probably best described as being an ideal of my own cultural Indigenous values. If you’re gifted something that someone has made, it’s something that you cherish. It’s not something that you part with easily or ever. It’s something that you are proud of. It’s something that you would share with other people in your community. So the idea of gifting our work to people in the community to steward is really about, “How can I share this most equitably in my community? How do I reach the people that I want this work to reach when those people are perhaps less likely to go to a gallery that the show might be hanging in?”

There are so many reasons that keep community and family apart from those of us who live in diaspora, and this is the most direct way that I can share what I’m doing with that community. I choose to give it to people who honor that, that honor the work that has gone into it, and they’re not just going to put it on their wall, keep it forever and one day it ends up in Goodwill, I hope. I mean, maybe. [All three laugh.] It’s all about who you choose to steward, right?

It really is about it meaning something more than just, “Here’s this gift that I’m giving to you as a present.” There’s a responsibility that comes with housing — I don’t even want to say artifacts — cultural objects. I think that when we make things, that’s what the outcome tends to be: a cultural object or a representation of ceremony or practice.

Lisa: And this notion of the conundrum of collecting and finances in the context of Art 25. There’s the obvious disconnect in how we weave these things together because it costs money to make work. It costs money to get together. It costs money to spend time. I think one of the things that our projects shine a light on is this paradox — it’s an inherent paradox; it’s not one that we’re able to resolve easily — that to say that we’re not going to sell our work still does not answer the question, who paid for the work? To me, that’s where not being validated by attachment to an institution really matters.

Between the three of us, the way that we navigate finances or projects is that we split everything equally. If Lehua and I need to travel to Honolulu because Jocelyn lives there, our flights might come to X amount of dollars, and we’ll still split that three ways. We’re trying to create situations where there are no barriers for any of us, where one of us who might have more money at this moment than the other therefore can do more. It’s challenging to foreground that as part of the project, but the project wouldn’t exist without a mindset that honors that among the three of us. That is a high-value situation.

Pier Carlo: I appreciate you bringing that up because otherwise I would feel like the graduate student watching “Art21” and wondering, “How do they do it?” So how do you fund Art 25?

Lisa: All kinds of ways. [She laughs.] I would say trade. Also, we earn money; we live; we have jobs; we pay for ourselves. We can’t wait for grants. We can’t wait. It’s not that we’re opposed to applying for grants. If an honorarium is offered as part of an invitation, we are delighted to accept it. We have a separate account that that money gets held in so that we can use it toward future projects.

But the idea that we’re self-funded, I think, matters a lot because it really makes the stakes higher. Grant-writing is also — for anybody that has done it, and I’m sure everybody in this conversation has, host included — a career unto itself. It does not serve the creative impetus that it’s trying to support, and it only makes your work valid when you receive a grant. It’s not that distant from capitalism; it just uses different language: “How well can you sell yourself, and who’s buying?”

While we live within the context of capitalism, we don’t have to just mimic or mirror the way that institutions have functioned. And we are not an institution. We’re a collective of artists collaborating across shared interests.

Pier Carlo: Lehua, you said a while back that really the goal of this is to be joyful in your work. What advice would you have for an artist in any field who might be hearing this who really wants to maximize her joy when it feels like a grind?

Lehua: Well, first of all, I think there’s aspects to all making, whether it’s art you put on a wall or food that you put on a table, that can become tedious because the ways that you choose the means to the end can be more or less tedious. It’s not separate from joy. I think enjoying the tedium of doing things, even the mundane, is part of the art.

From an Indigenous CHamoru perspective, there’s not necessarily a delineation between this type of art or this type of art. We just simply live a life where we create art through what we do to live. Every meal that’s lovingly prepared is an artful creation. The fan that your auntie weaves from coconut leaf is a beautiful thing on the wall if you decide to display it there, but it’s made to keep you cool.

I think that finding the joyfulness of life is about putting your love into it, whatever that may be. I mean, I can joke about becoming Mel Chin, but truthfully, I am Mel Chin in my own life. [They all laugh.] I’ve already achieved that success based on how I choose to live my life. It’s not for this standard of notoriety. It’s not for a standard of winning an award or receiving monetary gain or being famous. It’s the exact opposite of that. It’s, “How do you imbue your daily life with care and love and find beauty in that?” And when you put your hands to making something, you can call it art if you’d like, but I really do believe it’s reflected in daily living. And if an art practice is part of your daily living, it’s going to be joyful because you’re choosing to show up and do it.

Lisa: I mean … kind of.

Lehua: [Laughing] It seems like Lisa might have another perspective to offer.

Pier Carlo: Lisa, is there a riposte coming?

Lisa: [She laughs.] It was something about it being in your daily life and therefore being joyful, and I’m just literally looking at the pile of my daily life today. And I’m like, “It’s not joyful,” but that’s cool. It’s all part of the art. Literally every part of the pile is an art-related thing. It just made me laugh. I was like, “Wait a minute, I’m supposed to be happy right now?” Sorry.

Lehua: You always need a pessimist in your collaborative group. A pessimist is necessary because you need a foil for the optimist.

January 27, 2025